Overview: Rickenbacker and Intellectual Property

Under John Hall’s leadership, Rickenbacker developed a reputation for vigorously—some might even say aggressively—defending their intellectual property. And to be clear about my position on the matter: as they should. As anyone should! If you create something unique, other people shouldn’t be allowed to profit off of your hard work and creativity without your—the creator’s—permission. That’s just not fair.

Now some might say Rickenbacker takes it too far sometimes. Encouraging and aiding in the seizure of counterfeit guitars at the border? 100% appropriate. Sending cease and desist letters to builders whose designs look a little too much like trademarked designs? 100% appropriate. But to this day, just try and sell a “lawsuit era” Rickenbacker copy on eBay—a guitar made 40 years ago, well before Rickenbacker even established their trademarks—and it’ll get shut down quick, even if the ad clearly states what it is and is not. That feels a little excessive to some folks. But it’s the position the company has taken, and they don’t show any signs of backing down.

So what exactly are they defending, and what mechanisms are they using to do so? This is where we need to talk about trademarks and trade dress. But before we do that we should probably talk about the “lawsuit era guitars” first, as that was sort of the catalyst for where we are today. So let’s start there.

You’ve surely heard of “lawsuit era guitars” before, but what exactly were they? The short answer is they were very faithful—and in some cases exact—replicas of classic guitars built by primarily Japanese manufacturers between the mid 1970s-early 1980s. Not outright counterfeits like today’s Chibsons and Chickenbackers, they wore brand names like Burny, Greco, Tokai, Ibanez and many others on their headstocks, but were exact copies in all other ways.

Why did they exist? Because the demand was there! The 1970s was by and large not a “golden era” for the major US manufacturers, and these Japanese copies were in many cases actually better built guitars than the contemporary US built guitars—and cheaper to boot.

And while Fender and Gibson copies made up the majority of these guitars, smaller players like Rickenbacker were not immune. Here’s the catch, though. Most of the key design elements of these guitars—which dated back to the 1950s in some cases—had never been trademarked. John Hall himself admitted “my dad never filed a trademark in his life”.

So what even is a trademark? Your standard definition is “a unique symbol, word, phrase, design, or a combination of these elements used to identify and distinguish a product or service from others”. Note how I bolded “design”, as that’s the really important element in this context.

The big boys began filing trademarks on things like body shapes and headstock shapes in the early/mid 1970s once they realized the risk these Japanese copies posed. But in many cases the damage was already done. In John Hall’s words:

“Gibson and especially Fender were slow to file trademarks, as well as police all of the copies that were openly sold. When they tried to file new, more specific marks, they were granted but the various "infringers" were able to have the marks rescinded since they had essentially been public domain for years.”

Basically, people had been making copies of Strats and Teles so long those designs could no longer be considered “unique”. But SOME design elements—like Gibson’s “open-book” headstock and Fender’s headstock designs—were so unique and integral that they WERE given “protected/trademarked” status—the irony being that the Fender headstock was itself “borrowed” from a design by Paul Bigsby!

And so Gibson sued Ibanez in 1977 over Ibanez’s use of the open book headstock. The issue was settled out of court, but the fact that Ibanez—and all the other Japanese makers—stopped using the open book design should tell you which way the wind was blowing. That lawsuit marked the beginning of the end of the lawsuit guitar era.

Both Greco and Ibanez made very high quality Rickenbacker copies during the lawsuit era, but given that demand for Rickenbacker guitars was pretty low during this period so was the demand for copies. Basses were a different matter though, and lawsuit basses abound—Bruce Foxton of The Jam famously used an Ibanez 4001 copy during the band’s early years.

So Fender and Gibson were busy locking down their trademarks in the 1970s, but remember what John said: his dad never filed a trademark in his life. So Rickenbacker had a little catching up to do once John bought the company in 1984.

Here was the good news for Rickenbacker, though: there weren’t tons of copies out there. The case couldn’t be made that their designs had become public domain. So most of their trademark applications “stuck”—giving Rickenbacker a legal leg to stand on in protecting their intellectual property.

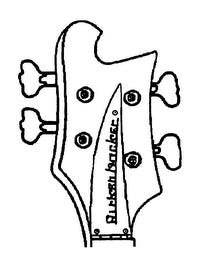

So what design elements are actually trademarked? Well, their logo, obviously:

Headstock shapes:

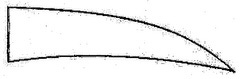

The truss rod cover shape —both with and without the logo.

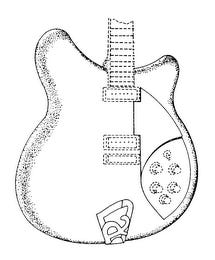

Cresting wave body shapes:

Semi-hollow body shapes:

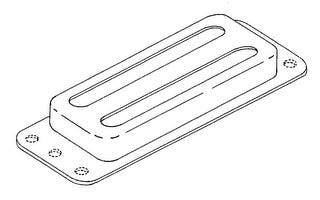

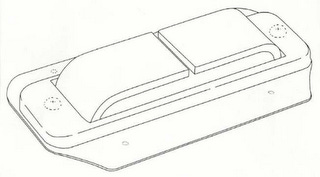

Pickup cases:

And the word “Toaster” itself (as applied to guitar pickups).

And that’s it. Which may not seem like much to base a campaign on as aggressive as Rickenbacker’s has been, but that’s where “trade dress” comes into play. And trade dress is kinda vague. Trade dress is all about a product’s “look and feel”, but the important part that it must be “distinctive” and/or “identify the source” of the product. If so, it’s protected just like a trademark is.

So, for example, while the “R” tailpiece is not trademarked it IS distinctive and DOES identify the source. It is therefore considered “trade dress” and is legally protected. Using that logic as a foundation, Rickenbacker has gone after companies that produce instruments of similar appearance to Rickenbacker models that aren’t necessarily trademarked. And usually the threat of legal action alone is enough to shut down production of any potentially infringing instruments.

But that hasn’t seemed to work in the pickup category. That seems to be the category their trademarks and threats don’t seem to carry much weight. They rather famously sued Jason Lollar back in 2013 over his horseshoe pickup….which he is still selling today. And there are plenty of toaster copies out there—including Lollar’s “broiler” pickup—but hey, none of them use the “Toaster” name at least!

Now the one area that Rickenbacker seems to “not care” about are the 1950’s “Combo” models. Certainly folks like Dennis Fano have made guitars WAY more than “influenced” by the Combo 600 and 800, and Bobby Nelson of Nelson Guitars made exact copies of the Combo 400 for years. But anything after 1958? Rickenbacker will cease and desist you to death.

There have been a couple of licensing deals—like the Chandler 555 and the Rickenbacker acoustics produced by Paul Wilczynski—but those have been few and far between. The basic underlying principle is that Rickenbacker just doesn’t want to devalue their brand by allowing other people—officially or unofficially—to use their intellectual property. And that is their right!

Good article Andy.

Would be cool to touch on the 'we don't cease and desist anymore' era that is now. Re: Harry White, and the many others that make 'near exact' models, including the TM's on the TRC. AliExpress, etc. Never a peep from RIC anymore... Or so it seems to me.