Overview: The 6/12 Convertible Guitars

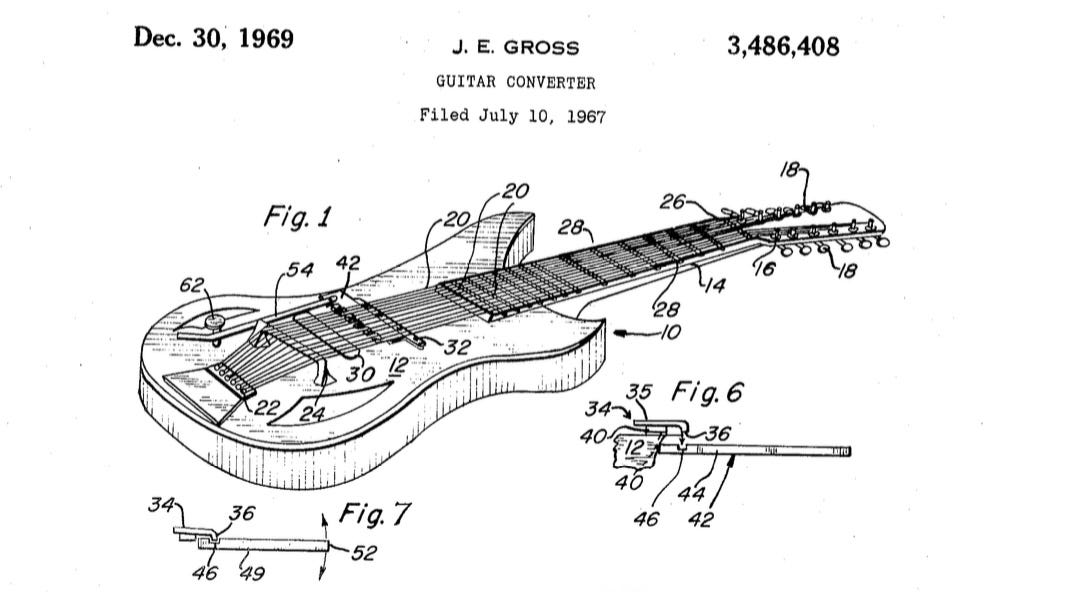

“A guitar converter device for conversion of a multi-string guitar to a guitar of fewer strings…by moving the strings so secured with the string engagement portion out of playing position, and a locking arm for holding the string engagement portion out of play.”

-US Patent Application, James E. Gross

Boy, it must have seemed like such a great idea to James E. “Jimmy” Gross of Glenview Illinois when he dreamed it up back in 1966—the ability to easily convert your 12 string guitar to a 6 string, and back again! No need to carry two guitars to the gig—or even OWN two guitars!—when with a flick of the wrist you could change back and forth!

If you want to get an idea of how much of a tinkerer the part-time musician/part-time inventor Gross was, try and wrap your mind around his personal Fender Jaguar!

Yeah, he had some ideas! And when it came to pitching this particular idea, who better to pitch it to than the kings of the 12-string guitar: Rickenbacker. And he must have been a heck of a salesman because he made the pitch in early 1966, two prototypes were shown at the NAMM show in July, a license agreement was signed in August, and the first guitars rolled out of the factory in December.

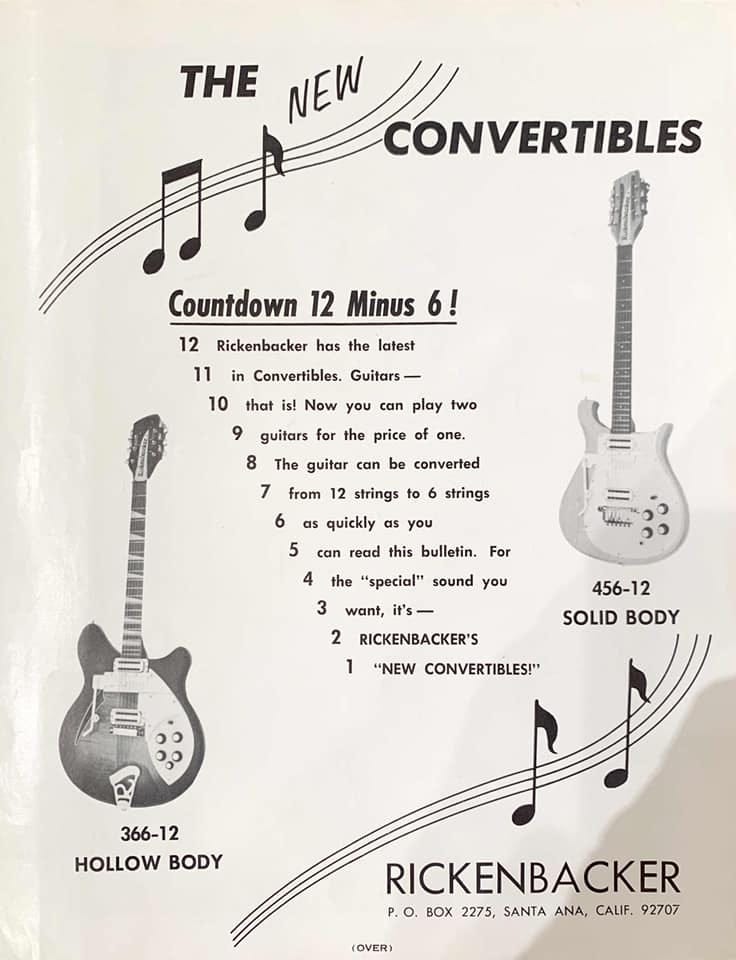

All of the 12-strings currently in the line got the converter treatment—and a special model number for those so equipped. The student/entry level 450/12 became the 456/12:

The Standard 330/12 became the 336/12:

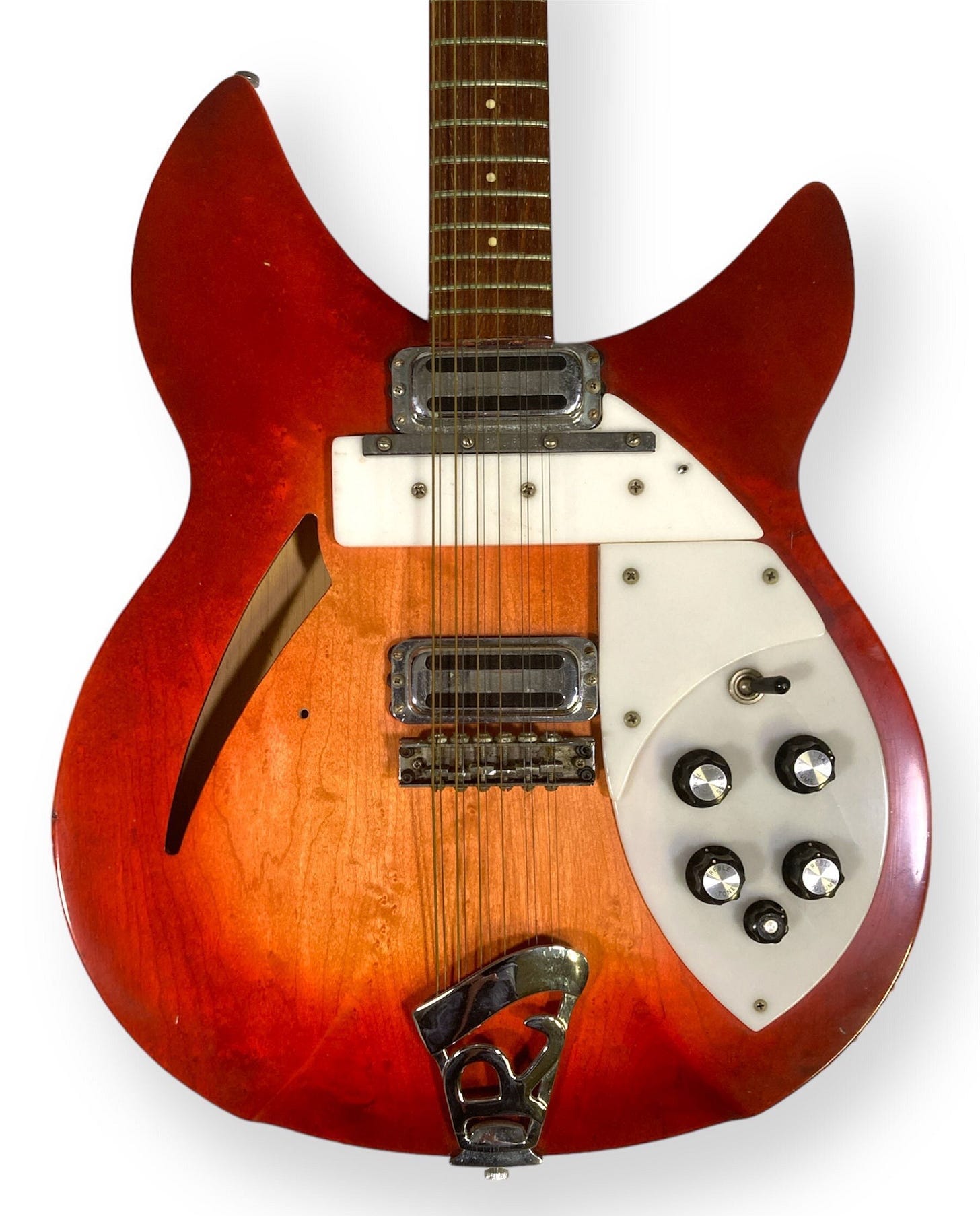

And the Deluxe 360/12 became…you guessed it, the 366/12:

Even the “Old Style” 360/12 got the convertible treatment:

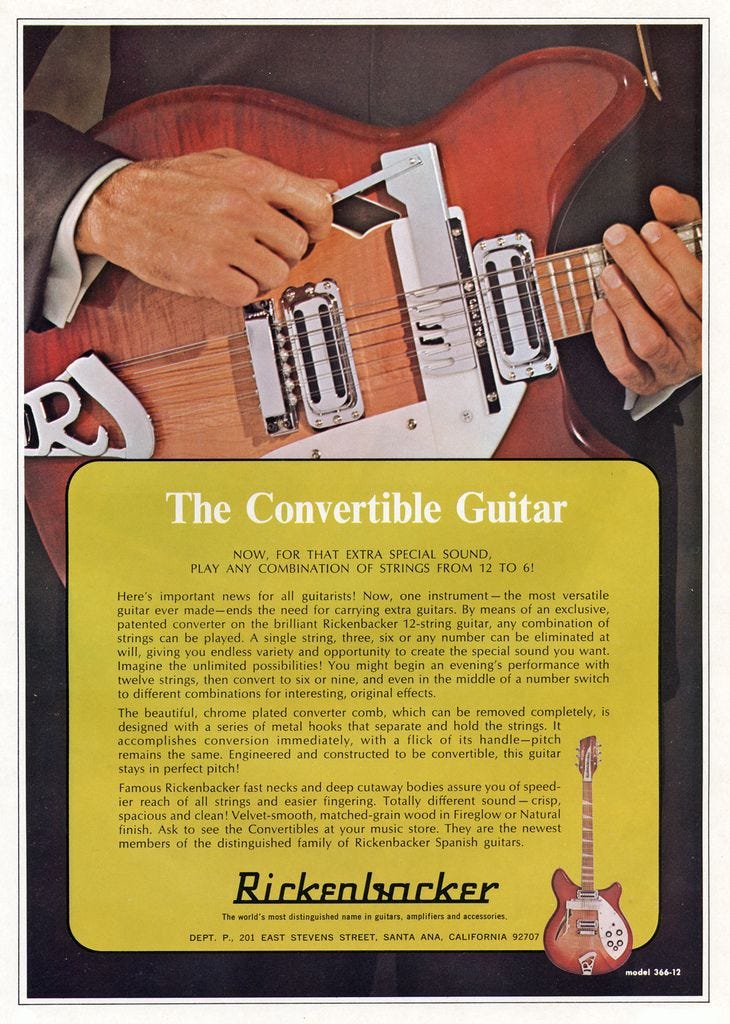

So we know WHAT the converter did. How exactly did it do it? Well, it all comes down to this little comb arm:

You can see it clearly here above without any strings in the “at rest” state. Notice in the photo below how the fingers of the comb follow the radius of the fretboard.

By disengaging the handle from the retaining screw, the comb can be slid underneath the strings and pivoted upward so the “fingers” on the comb slide over the octave string on each pair. Then the comb is pivoted back down, pulling down and muting the octave strings.

Lock the arm back on the retaining screw and voila—you now effectively have a 6-string guitar!

You probably noticed the thick plastic block the comb assembly rests on. Getting the height right was important, and the gap between the face of the guitar and the strings was too wide on the semi-hollowbodied guitars. Thus the mounting block that brought the assembly level with the upper pickguard. The integration was…perhaps a little bit less than elegant, but it worked!

The 456/12 had the opposite problem, however: the comb was too close to the strings. To overcome, the pickguard was cut out to allow the assembly to be lowered and more directly mounted to the face of the guitar. A very thin piece of black plastic sheeting was installed under the pickguards to fill the gap (and cover the routs!), held in place by the pickguard screws.

The 366/12 went into production in December 1966. The 335/12 followed in February of 1967, and the 456/12 in June. Initial market reaction was probably the same as yours: “that seems like a pretty cool idea!” And then people played them.

Deploying the comb wasn’t quite as simple as described above. I mean yes, that’s how it worked, but it was a little more fiddly than that. And its playability as a 6-string wasn’t that great. Which is unfortunate, because Rickenbacker had gone all in on the “Convertible Guitar”.

Around 40% of the 12-strings produced in 1967 had the converter attached. And the market said “meh”. Many were sold because that was the only Rickenbacker 12-string on the shelf. Most people who bought one either never used or just stopped using the converter. Others actually removed it entirely, figuring the extra screw holes were better than having the whole assembly in the way.

As a result, by late 1968 production of all three models wrapped, although they would stay on the pricelist until 1975. The license would expire and, seeing the market’s reaction to the Rickenbackers, no other manufacturer would express interest. Leaving Jimmy Gross free to tinker on his next idea.

Their short production runs mean they are relatively rare when compared to “normal” 60s 12-strings. But they’re actually worth less than their “normal” versions today. But they are a reminder of a time when companies went with their “gut” instead of focus groups—and how sometimes that didn’t pan out the way they’d hoped. And it IS a cool idea!

I owned a couple 366 - a Mapleglo and then an Azureglo - at one time. I was travelling a lot and made thought it would save me some space. The quick change comb was anything but as the pulled down added tension meant that guitar retuning was required. The best part was instant Nashville Tuning set up available! Nice idea but the mounted comb block really killed the acoustics of the semi hollow body. My ‘68 Azureglo was mint when I got it and remained mint when I moved it on.

I wonder if Mr Gross was also responsible for the equally “sounds great in theory, not great in practice” 4001 bass mute assembly. 😅