Terminology: Neck-Through Construction

Almost all guitars are made of two major components—the neck and the body—that are joined together in some fashion. The neck can be attached to the body via mechanical means like screws (a “bolt-on neck”), a mortise and tenon or dovetail joint usually reinforced by a chemical adhesive like glue (a “set-neck”), or it can be an integral part of the body itself (“neck-through”). While Rickenbacker has used all three methods over its history, it is notable for having utilized neck-through construction continuously for longer than any other manufacturer. Let’s talk about it!

So quickly, set-neck is the “classic” method. It’s how stringed instrument necks have been attached to their bodies for centuries. Almost all acoustic guitars still use this method, and many electric guitar makers—including Rickenbacker—still use this method today. Think 360, think Les Paul.

I haven’t been able to conclusively nail down when the “first” bolt-on neck guitar appeared, but it certainly gained prominence in the 1950s thanks to one Clarence Leonidas Fender. Much easier—and cheaper!—than the traditional set-neck, the bolt-on neck makes mass production much faster—and it’s much easier to adjust or repair. Think Telecaster, think Precision Bass.

And finally we have neck-through. By far the least common method thanks to its difficulty and expense, the neck is part of the body itself—one solid piece running from headstock to tailpiece, with body “wings” attached to each side. It’s a much stronger design, and in theory provides a bit more sustain by having each end of the string attached to the same piece of wood. Think 4001, think reverse Firebird.

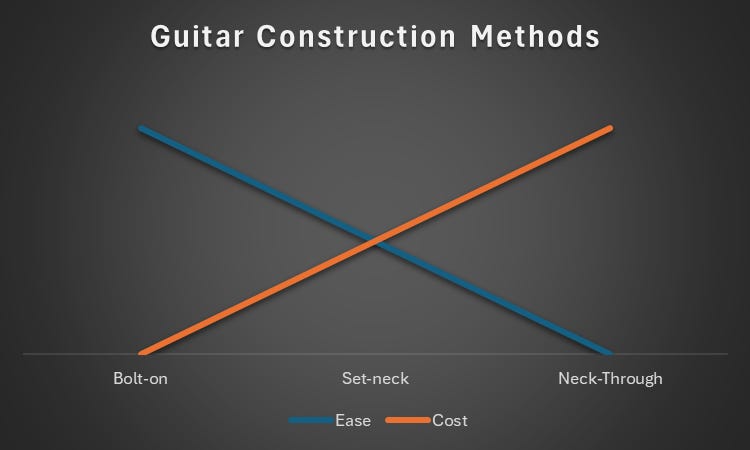

If you plot them out in terms of ease and cost of construction, you get something that looks like kind of like this:

The cost and effort of neck-through construction has largely relegated neck-through construction to the world of high-end models and boutique makers. Despite that, Rickenbacker has been making neck-through guitars nonstop since 1956. But they weren’t the first to do so.

The internet will tell you that honor goes all the way back to 1936(!) to Paul Tutmarc and the Audiovox 736–the very first electric bass guitar! I’m not convinced the internet is correct. Paul Tutmarc did build a neck-through electric upright bass as early as 1932, but I’m not certain—based on the limited photographic evidence of the three extant 736’s—that they were neck through. Your results may vary!

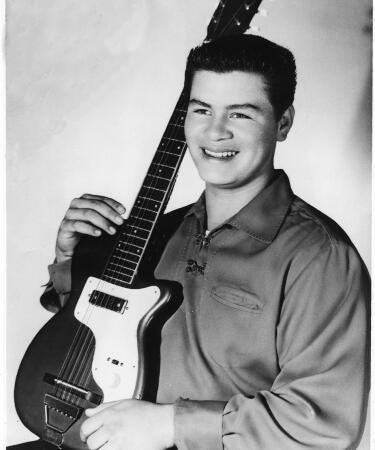

I’m much more certain, however, that the first “production” neck-through electric guitar was the Harmony H44 Stratotone, produced between 1952 and 1957 and made famous by Ritchie Valens.

Funny to think in today’s context that this neck-through guitar was a cheap, entry level model!

Similarly, when the tulip-shaped Rickenbacker Combo 400 (click to learn more)–the company’s third solidbody electric guitar—first appeared in 1956, it was the entry level model. They didn’t try to hide the model’s neck-through construction!

While it’s fairly clear from the picture above, here’s a 3D rendering of an “exploded” Rickenbacker neck-through bass to show you what all the components look like apart (although the routing is done after assembly):

Why build the guitar this way? Period literature calls out the construction method, but ascribes no benefit to it. So who knows? My theory is this: getting the neck aligned properly—especially in those early hand-made days—is one of the most critical bits in guitar manufacturing. Building it all out of one piece of lumber eliminates that concern!

As Ron O’Keefe reminded me, while the wings are glued on today, the very first Combo 400s were held together with bolts that ran side to side through both wings and the neck. The holes for the bolts were then covered with a metal cap.

The bolts were dropped pretty quickly and briefly replaced by both glue and staples before the staples were dropped as well.

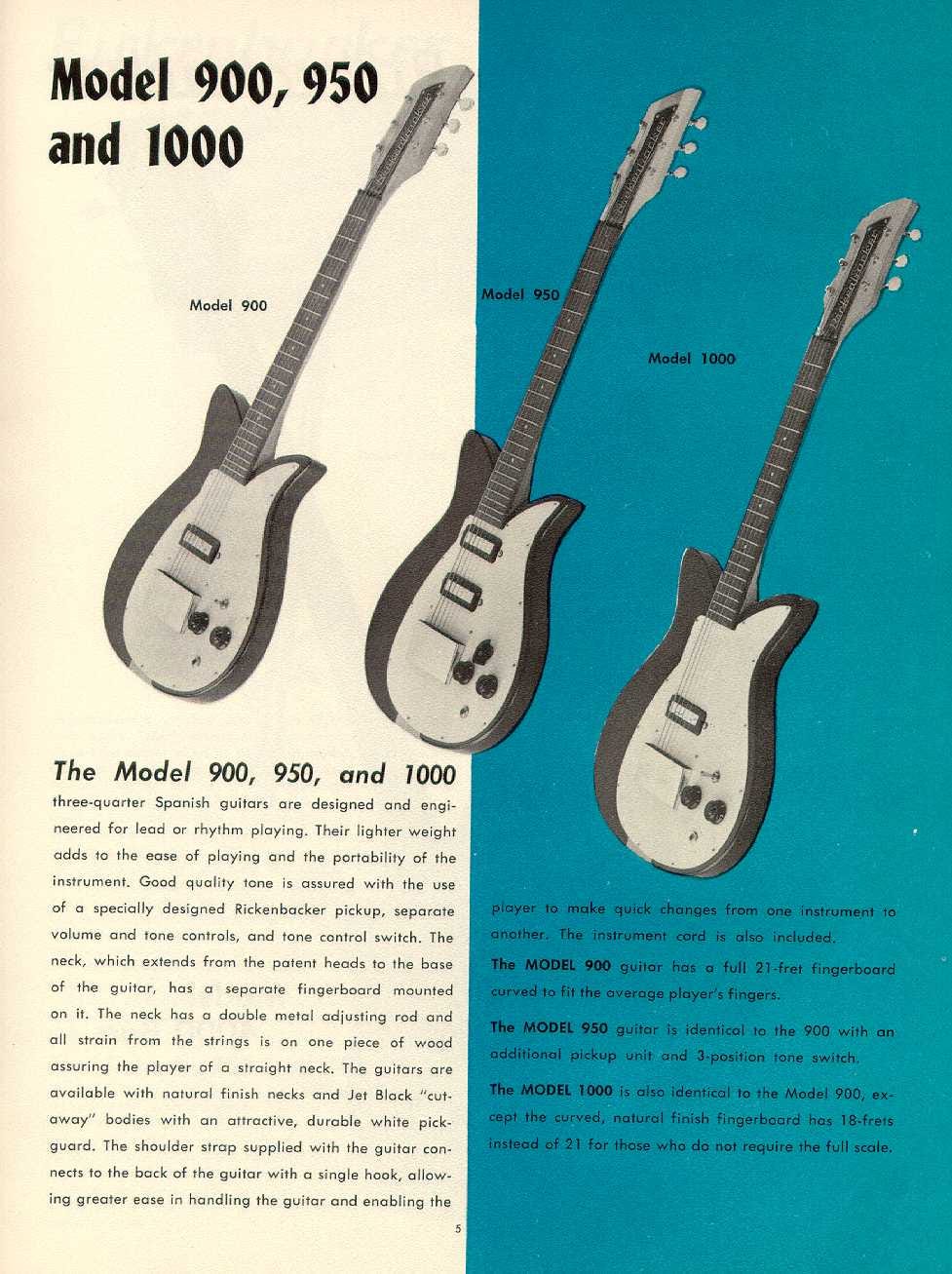

From the Combo 400 on, neck-through construction would be the norm for Rickenbacker solid-bodied guitars—starting with the FIVE new neck-through models that would appear in the 1957 catalog: the Combo 450, the short-scale 900, 950, and 1000, and the 4000 bass.

As the cresting wave replaced the tulip on the 400 guitars, it kept the neck through construction.

While very early cresting wave 400s maintained the “natural neck/painted wings” look with visible “notches” between the two at the bottom of the guitar, it didn’t take long for the notches to go away and the entire body section to be finished one color—although the neck remained natural.

In 1959 the neck and headstock would become body colored as well.

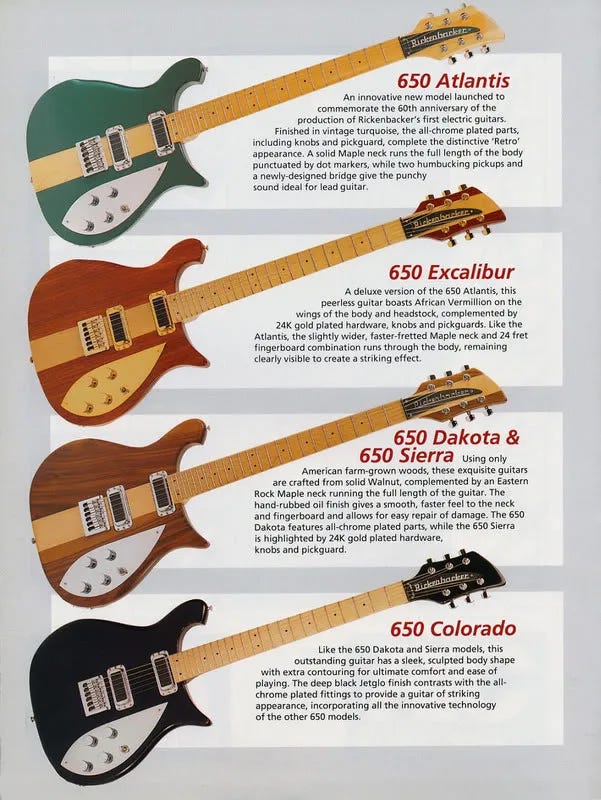

This would be the formula all solidbody cresting wave guitars—420, 425, 450, 460 610, 615/1995, 620, 625—would follow until the “modern” cresting wave 650 models appeared in 1992.

Well, mostly. You see, Rickenbacker launched the 425-based ES-17 in 1963, and for the first couple years of its life that’s what it was—a 425 with a different tress rod cover. But in mid 1965, things get kinda confusing. First of all, the 425 split into two models: the NOT A BOYD vibrato equipped 425, and the vibrato-less 420. The “new” 425 would maintain its neck-through construction but, in an attempt to speed up production and drive down costs, in mid 1965 the 420 and ES-17 would change to a set neck. The 420 would remain set-neck until its last production run in 1981.

And just for the hell of it, from February through June of 1966 the 450/12 was set neck. Why? Your guess is as good as mine.

Back to the 650! Most of the modern 650 models—the Atlantis, the Dakota, the Excalibur/Frisco, and the Sierra—harkened back to those earliest neck-through models with natural necks and colored wings—even if it was simply differently colored woods. Only one—the Colorado—would follow the modern monochrome scheme.

There’s one other guitar that got a through neck: the 90th Anniversary 480XC—a callback to the original 1970s model 480 which, funnily enough, had a bolt-on neck!

Basses are probably the “most famous” neck-through Rickenbacker models, with the 4000, 4001, 4002, 4003, and 4004 all following this template (apart from the 4000 and 4001S which were, for cost reduction purposes, set-neck from 1972 to 1985).

Unlike guitars, basses never had natural necks/painted wings, although 1958-59 4000s had mahogany necks and maple wings, giving the guitars a two-tone look.

This look would be reversed on the 4004 Cheyenne, 4004LK Lemmy Kilmister Signature Limited Edition, 4003W, and 4003AC Al Cisneros Signature Limited Edition models which all featured a maple neck and walnut wings.

So why has Rickenbacker stuck with this relatively uncommon and expensive construction method for most of their solidbody guitars and basses for so long? Cause that’s just how they do it, I reckon. If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it!

Want to learn more about…everything else? Check out the rickenbacker101 site map and see what’s already been covered! Have a suggestion about what we should tackle next? Drop it in the comments and we’ll add it to the queue.

FYI - neck through construction is on the Gibson Reverse Firebird. Non-reverse Firebird from 1965 became glued set neck. Reverse build became a big cost issue along with its carved headstock.

Great article! A 71-72 4000 was my first neckthrough bass, after initially owning a Fender P.

They were so different in feel, playability, and sound….I very quickly gravitated towards the Rick!

Leo Fender’s last company, G&L, has current advertising touting the Fender factory in California as

“the birthplace of bolt-on”.