Terminology: Conversion Varnish

I’ve spent a lot of time staring at a blank page trying to figure out how to approach this topic. I could just say “Rickenbacker has used a conversion varnish finish on their guitars since 1959” and be done with it, but what does that even really mean? Heck, I didn’t really understand just what conversion varnish really was before I started my research for this write-up. I think I do now, and it is my hope that by the end of this you do too!

And that’s the ambition here: to tell you what conversion varnish is, what makes it unique, and why Rickenbacker uses it. If I can do that…well, I’ll feel pretty good about myself!

I should probably warn you that we’re gonna get pretty technical here. I’ll try to keep the language as clear as possible, but there’s just no way to avoid it given the topic. Apologies in advance!

Let’s begin with some really generic and basic terms. The first of which is “lacquer”. We use that word all the time when we say things like “Rickenbacker’s lacquered fingerboard”. Now I just told you that Rickenbacker uses a conversion varnish finish, so is “lacquered fingerboard” incorrect? Well, technically, yes, because a lacquer is thermoplastic and a conversion varnish is thermoset and oh crap there’s two new terms we have to deal with now!

So what do all these words actually mean? Well, not to get all word-geeky here, but if we break down the words “thermoplastic” and “thermoset” they’re already telling us what we need to know. “Thermo” means heat, then add “plastic” which means moldable or “set” which means…set! Clear? Well, maybe we can add a little more detail.

A thermoplastic finish is composed of a resin (a solid) held in solution in a solvent (a liquid). When applied, the finish “cures” by the evaporation of the solvent—usually triggered or accelerated by the application of heat—leaving only the resin in place. There’s our “thermo”! The reintroduction of the solvent will “melt” the resin back into solution, making repair or removal easy. There’s our “plastic”!

Mud is a good analogy for thermoplastic. It’s composed of a “resin” (dirt) held in solution in a “solvent” (water). Step into a mud puddle, and mud will get all over your shoes. As the water evaporates, the dirt will remain caked to your shoes. Your shoes now have a dirt “finish”. If some of the dirt flakes off, rub a little more mud on and around the bare spot and when it dries you will have “repaired” your finish. Spray your shoes with the garden hose and you have now “reapplied” the “solvent”, and the “finish” will come right off.

A thermoset finish, on the other hand, is made up of components that undergo an irreversible chemical reaction called cross-linking—a bonding, if you will—when exposed to a curing process like heat. There’s our “thermo”! And, as noted above, this process is irreversible. There’s our “set”!

A good analogy here is a cake. You dump a bunch of discreet ingredients into a pan—flour, sugar, eggs, water—mix them all together, then put it in the oven. After it has baked—or cured—it is no longer all the individual ingredients you added to the pan, it is a cake. And you can’t unbake a cake.

OK, we’ve defined thermoplastic and thermoset so let’s go back to “lacquer”. Laquer is kind of a catch-all today, but it’s a catch-all for thermoplastic finishes. The term is derived from finishes both practical and decorative made from the sap of the lacquer tree found in Asia for over 9,000 years. But the “modern” definition of lacquer really begins with “shellac”—which is a finish made from the resin secreted by the female lac bug dissolved in alcohol (sure sounds like a thermoplastic to me!) which has been used for over 3,000 years!

So a lacquer is a thermoplastic and we’ve already said that conversion varnish is a thermoset, so we ARE technically wrong when we talk about Rickenbacker’s “lacquered” fingerboards. But what the hell, only pedants will call you out on it so call it what you like—we all know what you mean!

Okay, we’re finally making it to guitar finishes! Most modern finishes today are thermoset. Polyester and polyurethane—your “poly” finishes—are thermosets. Poly finishes are easy to apply, more durable, and cheaper than thermoplastic finishes. More environmentally friendly, too, with fewer volatile organic compounds (VOCs) released in their application. They’re also newer, not really gaining widespread market usage until the late 1960s

Your “nitro”—or more properly “nitrocellulose”—finishes are thermoplastic. Cellulose or wood fibers are the base resin, and things like acetone and toluene act as the solvent. They predate the poly finishes, and continue to be used on higher end and vintage reproduction guitars. As you’ve already heard, Rickenbacker used a nitro finish until 1959 when they changed to a conversion varnish.

It took us a while, but we finally made it to conversion varnish! So what exactly is a conversion varnish? And what makes it different from everything else we’ve discussed so far?

Well, it’s a thermoset just like our poly finishes, but the major difference is that the cross linking components—the base resin and an acidic catalyst—are kept separate until just before they are applied. In most other thermosets the solvents that keep the paint liquid will keep the other components from cross-linking, but the bonds are so irresistible in a conversion varnish they have to be kept separate.

Upon combination the two components begin to cross-link, accelerated by the curing process. The cross-linking actually continues after the curing is done, ensuring an extremely durable finished product.

A good analogy here is a two part epoxy. Separately, each component is just a gooey mess. Mixed together, the two dry to form an unbreakable bond that will hold any two things together.

So that sounds kinda complicated. Why bother? That’s a good question. Especially given that Rickenbacker and Taylor are the only “major” guitar companies to have significantly made use of conversion varnish finishes. So why?

Well, conversion varnish is hands down the most durable of all the finishes we’ve discussed—very resistant to stains, minor scratches, and the like. Much stronger than nitro finishes, and more flexible than poly finishes. A sharp strike can knock a chip off a thick poly finish, but the same strike will only dent a conversion varnish finish. So a major benefit to the end user.

The benefit to the manufacturer—and this is true of all thermosets—is just how fast you can crank this finish out. Thermoplastics like nitro have to dry outside-in to harden—and it can take several days of curing for each coat before the finish is “set” enough to go into buffing and assembly. Not so for thermosets. The catalyzation occurs throughout the entire finish at the same time, and the finish is set within a matter of hours, not days.

So why don’t more people use conversion varnish? Because it’s quite expensive and poly finishes have many of the same benefits but cost a whole heck of a lot less. And marketing has pushed the magical and mythical properties of nitro finishes “just like they used in the old days” to fill the “premium finish” slot.

And let’s talk about that for a minute coldly and dispassionately. What is the real PURPOSE of a guitar finish? Protection and cosmetics, right? So in terms of protection, nitro is objectively the worst of the types of finishes we’ve discussed. There’s no debate there. They’re (usually) thinner than the alternatives, they’re “softer” and therefore easier to scratch, yet at the same time they’re so brittle they crack or “check” when a guitar is exposed to environmental changes…as far as protection goes they kinda suck. So what about cosmetics?

This is where things get subjective. Brand new, they look great. No doubt. But all of them do. You can make the case that some poly finishes look plasticky, but new out of the box they all look pretty good.

But nitro ages differently than the others do. Because it’s thinner, because it’s less durable, because it’s susceptible to environmental changes…it wears more heavily more easily. And people like that. A whole new industry has arisen dedicated to making new guitars look old!

People will also tell you dead seriously that the thinner nitro finish (and we’re only talking about thousandths of an inch here!) lets the wood “breathe”. That it makes it “more resonant”. Ok, sure. You can likely make that case on acoustic guitars, but a solidbody electric guitar? Please. The pickup is FAR more important to the sound than a couple thousandths of an inch of finish. But such is the power of marketing!

So the market equates nitro with “quality”, poly with “cheap”, and conversion varnish as “what’s that?” So why has Rickenbacker stuck with conversion varnish? Because they think it’s the best. That’s the answer—it’s that simple.

The formula and suppliers and process Rickenbacker has used have changed several times over the years—we know from John Hall that Fullerplast, Sherwin-Williams, and Lawrence-McFadden are among the suppliers that have been used over the years. But the biggest change came in 2009-2010 when they switched to a UV-cured product.

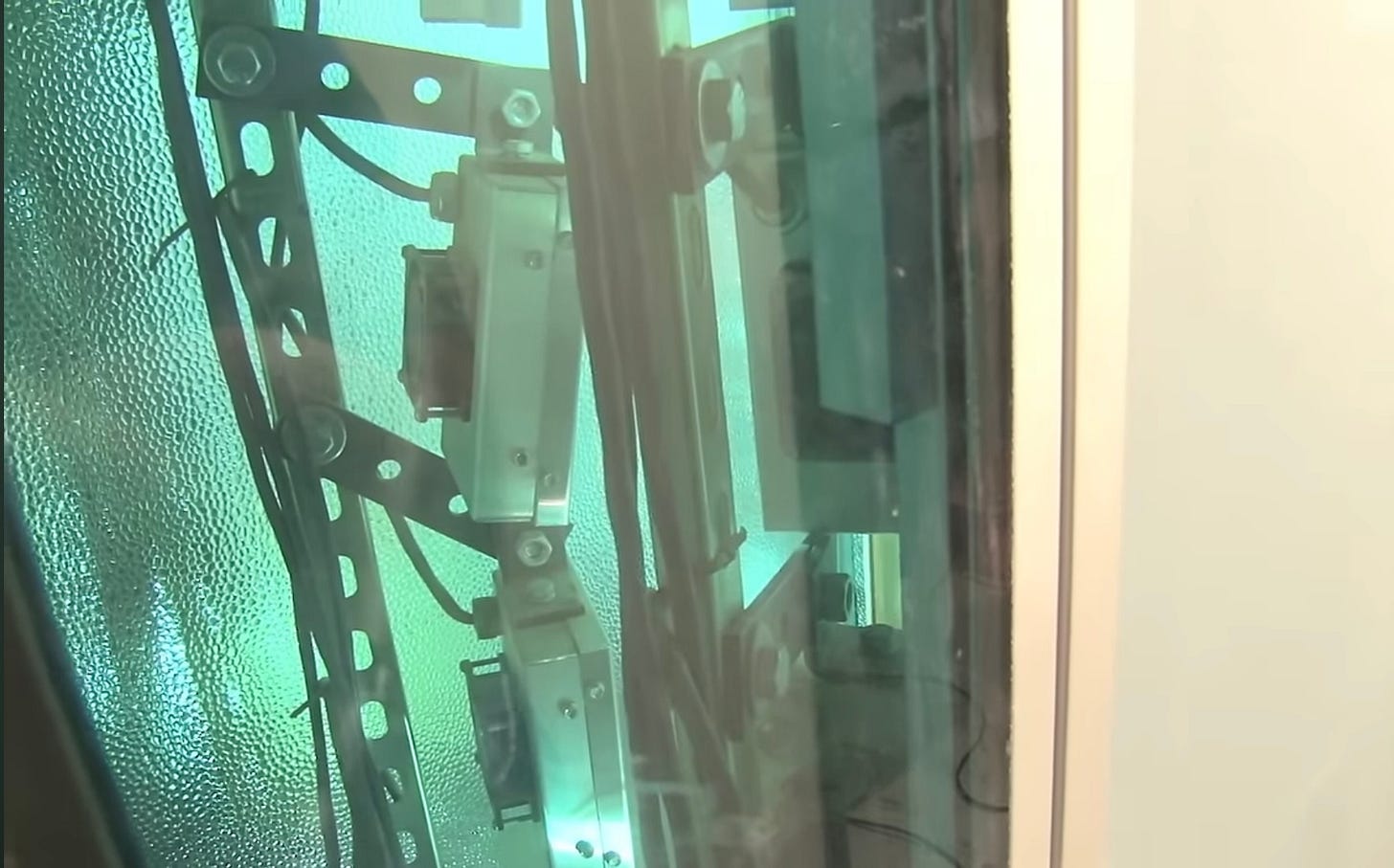

There were two huge benefits this change. First, the UV curing process is even faster still. How fast? Per John Hall, three minutes and forty-five seconds in the UV booth does the trick.

Secondly, there are almost no VOCs in the UV-cured formulation. It was actually a tightening in California’s emissions limits that was a key driver of the change to the UV-cured formula. So all the benefits of a conversion varnish, faster and greener. Win-win-win!

So we now know what a conversion varnish is and why Rickenbacker uses it. Mission accomplished, no? Well, technically yes. But before we go let’s spend a few minutes talking a bit about the finishing process itself, because it’s not just “one coat of paint” we’re talking about here. It’s a whole bunch of layers. How many? It depends, but probably an average of eleven to fourteen!

And not to completely derail everything we’ve discussed up to this point, but we’ve really ONLY been talking about the clearcoat up to this point. There are three discreet “strata” of finish on a Rickenbacker, and they’re not necessarily all conversion varnishes!

By the same token, not all strata on Fender’s beloved vintage nitro finish are nitro! For years, Fender (and Rickenbacker!) used a product called Fullerplast for the sealer coats. The sealer is the first layer of the finish and its job is to create a smooth non-porous surface for the topcoats to adhere to. And guess what? Fullerplast is a conversion varnish! Fender’s 1960s nitro finishes had a conversion varnish foundation!

On top of a couple of sealer coats we have the color or base coats. Mapleglo actually has no color coat…we’re just seeing the natural maple. Fireglo gets applied in one coat, light in the middle, heavy on the edges. Fun fact: Rickenbacker “bursts” are not dyes or stains like on a PRS or a Gibson…they do not come directly into contact with the wood. They are sitting on top of the sealer coat.

Most solid colors like Jetglo get multiple coats to ensure complete, even coverage. If a coat is too heavy it will run or sag, if it’s too light you’ll see through to the wood grain underneath. Historically automotive paints have been used for this layer which, while thermosets, are not conversion varnishes.

Now remember that each of these coats has to dry or cure before the next one is applied. Prior to the UV-cured topcoat(s), the average total curing time—JUST the curing time—for all the coats combined was around fourteen days! There is also sanding between coats (but not EVERY coat) to ensure a perfectly smooth and shiny finished product on top of that cure time.

Jumping back into the process, the binding is not masked during this process, so before the clear coats can be applied it is scraped clean with a razor blade by hand to remove the overspray and ensure nice clean edges between the binding and the colored finish.

And now we come to the clear coats. The most numerous by far—somewhere north of five and south of ten—which shows you what a game changer the UV-cured finish was. Three minutes forty-five seconds and you’re done!

The total thickness of all of these coats? Around .005-.007 inches. About the thickness of a human hair. A couple hours of buffing and polishing later, and the finish is…finished!

But what about “ambering”! You haven’t talked about ambering! Fair point. Over time, exposure to UV light can cause the clear coat to yellow or amber slightly. That’s why guitars with White finishes are mostly cream-colored now. It’s why some Jetglo guitars can look green in direct sunlight. And it’s why older Fireglo guitars have that lovely amber center.

Good news/bad news depending on how you feel about that amber tint: new guitars shouldn’t do that. The switch to UV curing meant a change in the formula to include UV stabilizers to fight that ambering. And with over fifteen years experience so far, it appears to be working.

So. Can you now explain what a conversion varnish is, how it differs from other types of finishes, and why Rickenbacker uses it? If so, I’ve done my job well. If not, let me know and I’ll try my best to make it clearer still!

Want to learn more about…everything else? Check out our handy site map to see what we’ve already covered. Got something you’d like to see covered? Drop it in the comments and we’ll add it to the queue.

Hi Andy. Great post, as always. What’s not mentioned in the post is that some of the guitars/basses produced during the period of transition to UV cured finishes have serious finish problems. I know because I’m the unfortunate owner of two basses from this period. It seems that Rick hadn’t quite perfected the process when they started using it.

Great discussion, Andy!