Terminology: The Kauffman Vibrola

The first guitar tremolo

Let’s put this into context. In 1958, when Rickenbacker’s “modern” usage of the Kauffman Vibrola began, the Bigsby Tremolo was seven years old, having debuted in 1951. The Fender Stratocaster’s “synchronized tremolo” arrived in 1954. The Kauffman unit that appeared on vibrato-equipped Rickenbacker Capri models, however, dated all the way back to 1928. To say it was not state-of-the-art is putting it kindly.

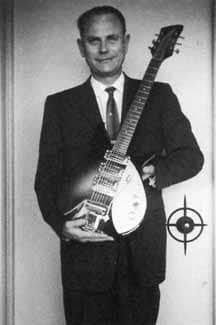

When discussing the early days of the electric guitar—especially in Southern California, the industry’s epicenter—you see a lot of the same names pop up again and again: Paul Bigsby, Leo Fender, Paul Barth, and one Clayton “Doc” Kauffman.

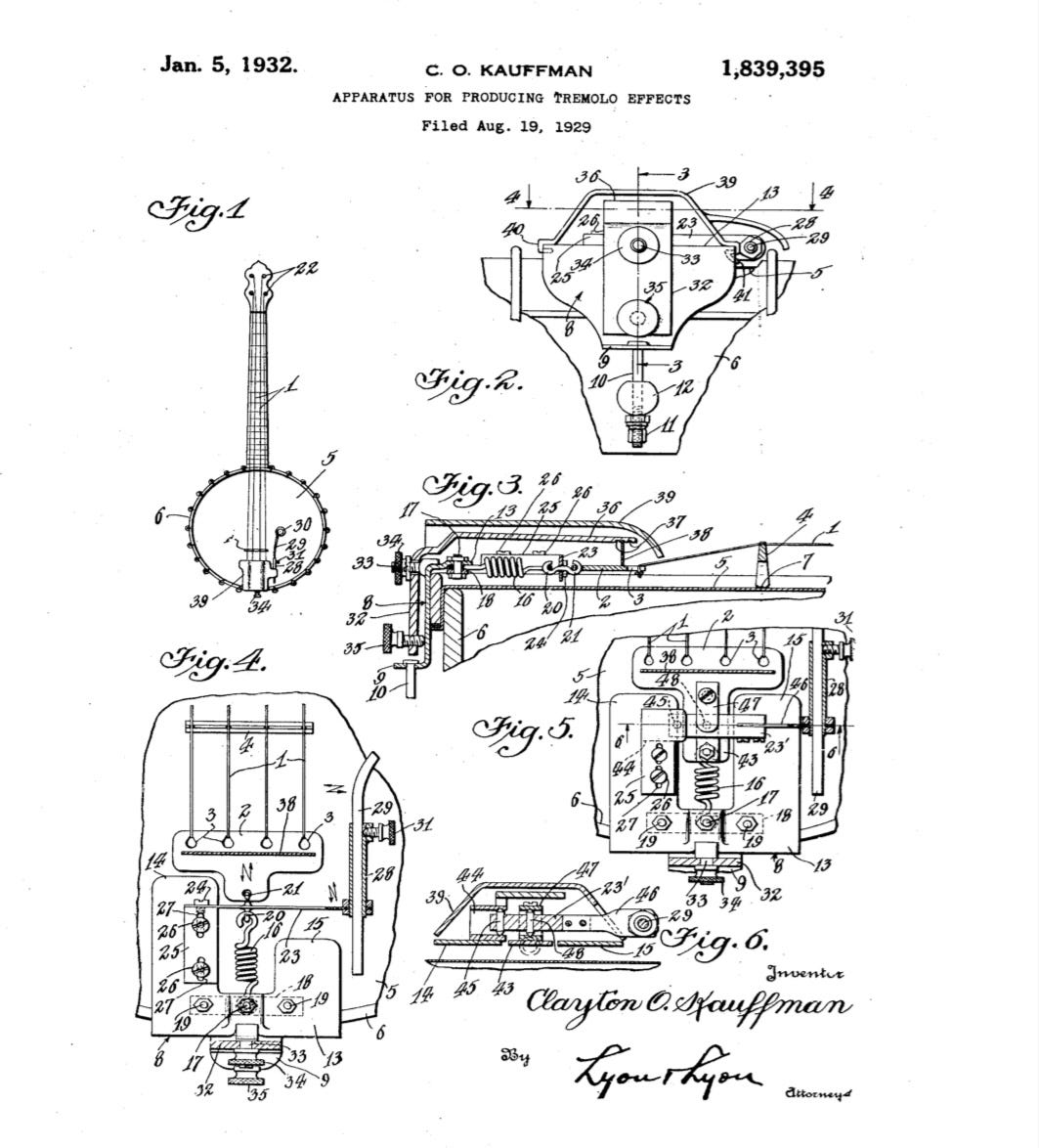

Kauffman played both Spanish and Hawaiian style guitar, and he wanted to find a way to get the Hawaiian guitar’s fluid sound out of the Spanish guitar. An inveterate tinkerer—he even held a 1944 patent for a home dishwasher—in 1928 he invented a simple mechanism that allowed the player to create a light pitch-changing effect. He applied for a patent in 1929 and it was granted in 1932, making the Kauffman Vibrola the very first guitar tremolo.

The mechanics of the Vibrola were…something of a dead-end, if we’re being honest. There’s a pretty good reason why all the systems that followed worked differently. But here’s how it worked.

You’re familiar with how both the Bigsby and the Strat tremolos work. While the mechanics of the two are different, the principle is the same: pull the handle up, string tension increases and pitch rises, push the handle down, string tension decreases and pitch lowers. That isn’t how the Kauffman works.

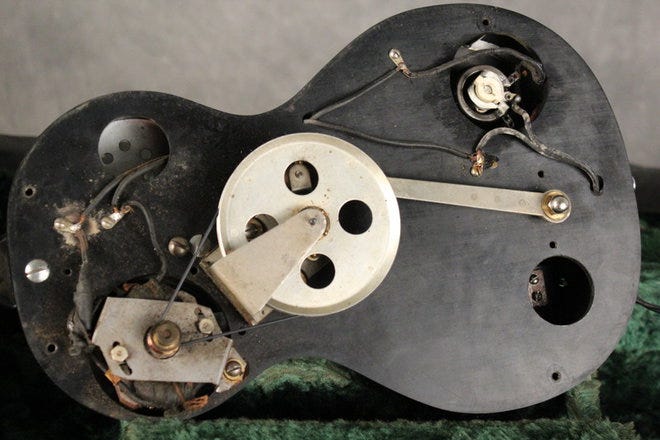

You’ll notice in the picture above that the tailpiece the strings attach to on the Kauffman sits on a central pivot. Its handle doesn’t move up and down—it moves side to side. When you move it, the tailpiece moves side to side on that pivot. This means that tension is increased—unevenly—on half the strings, raising their pitch. At the same time, tension is decreased on the other strings, lowering their pitch.

If that sounds a little…strange, it is. But that’s because you’re thinking about it in the modern context of what a tremolo is supposed to do—not in the context in which it was designed: making a Spanish guitar sound like a Hawaiian guitar. In that light, well, it’s still weird—but it makes more sense.

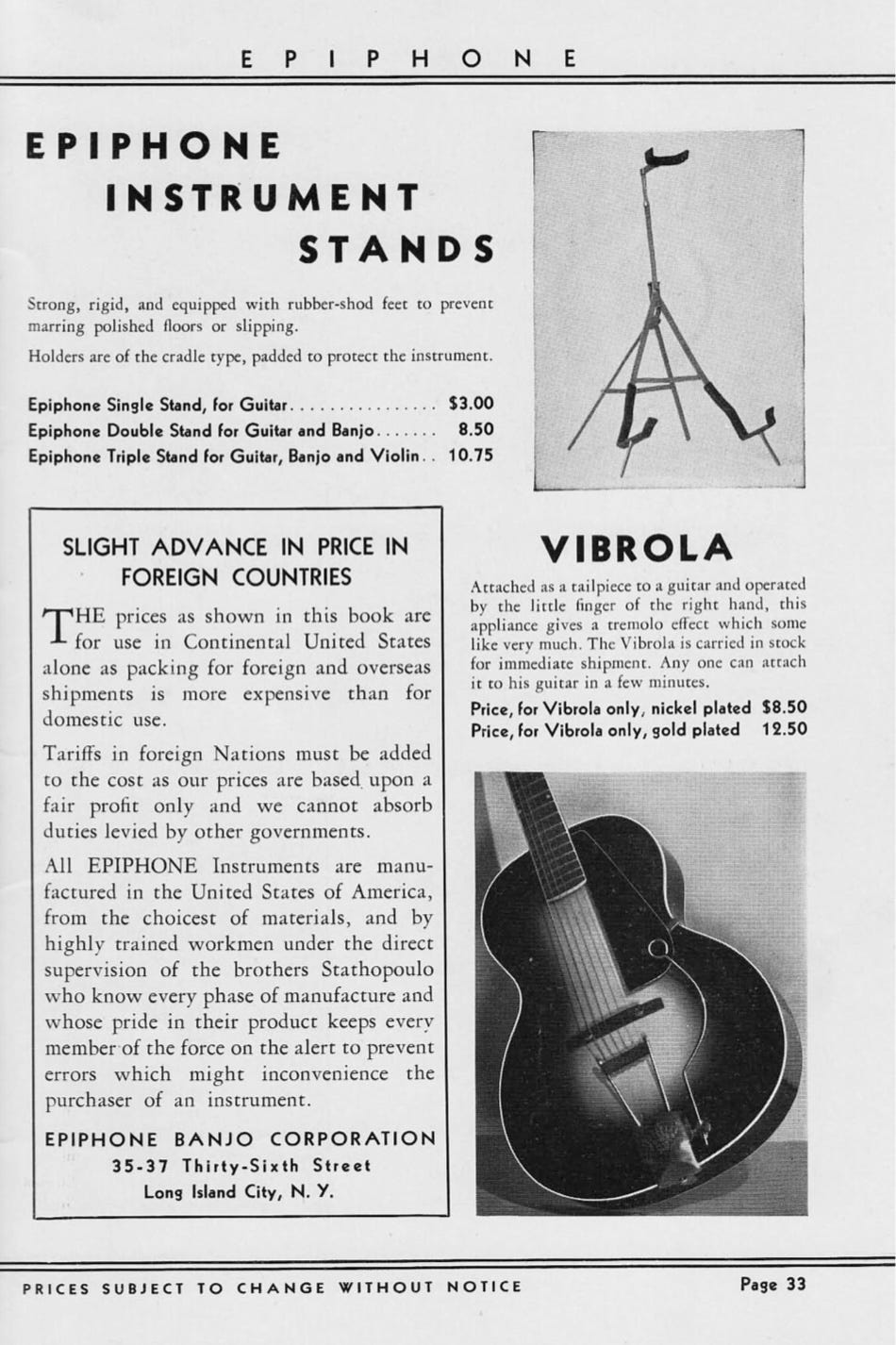

The earliest reference I’ve found to mention Kauffman’s invention appears in the 1934 Epiphone catalog, where it was offered as an aftermarket accessory. While it was not fitted as standard to any of their models, the fact that a market leader like Epiphone would consider it interesting enough to add to their catalog speaks volumes about the Vibrola’s novelty. The catalog even includes multiple pictures of Epiphone artists playing Vibrola-equipped guitars.

But it wouldn’t be one of the market leaders like Epiphone or Gibson to fully embrace the Vibrola and offer the first guitar with Kauffman’s invention fitted as standard. That honor would instead go to an upstart from California: Electro String Instrument Corporation—the corporate predecessor to modern Rickenbacker.

And it makes perfect sense that it would be Rickenbacker—who had built their business on the first electric Hawaiian steel guitars—who would want to apply Kauffman’s Vibrola as they tried to make inroads into the Spanish guitar market. After all, the whole point of the Vibrola was to make a Spanish guitar sound Hawaiian.

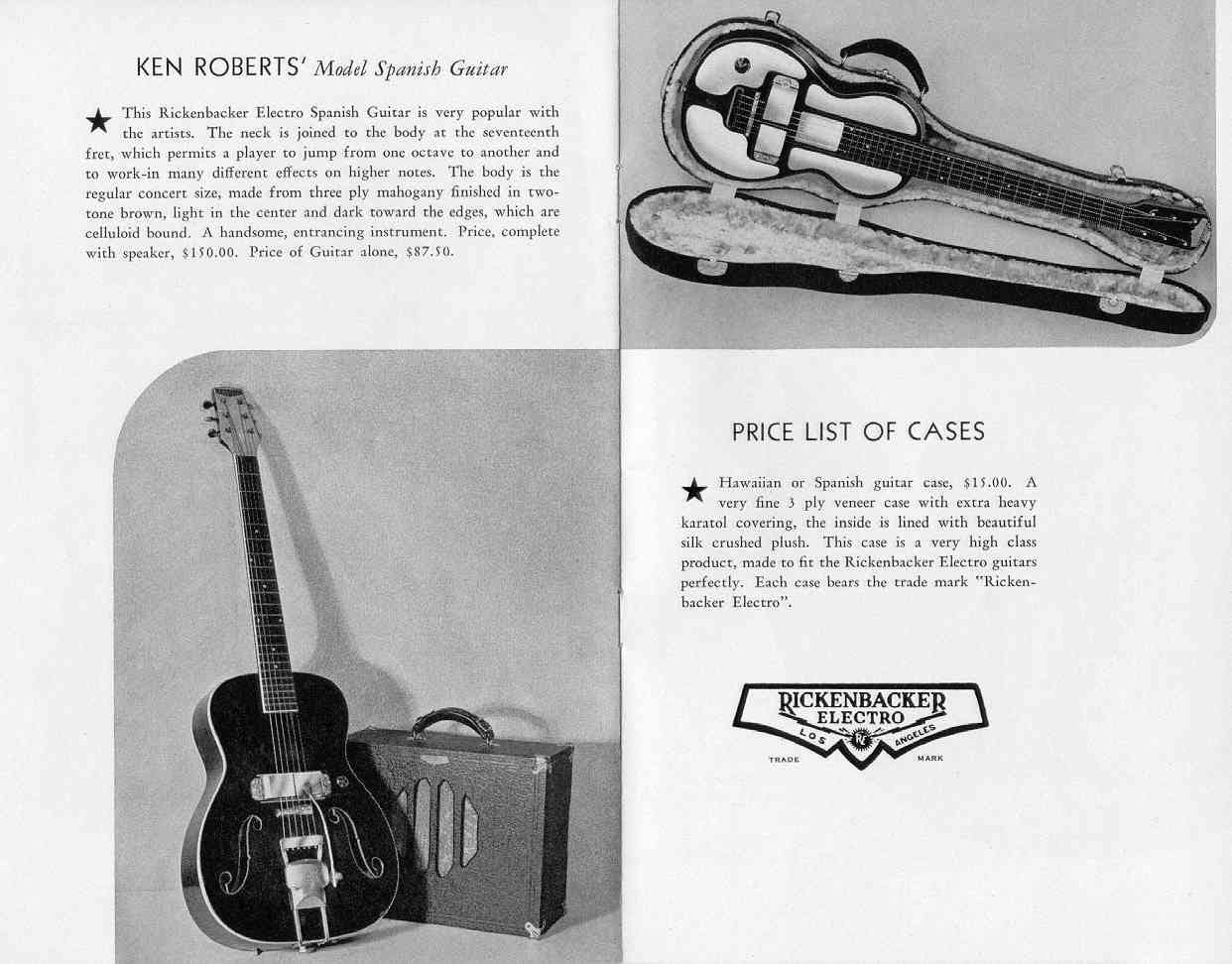

And so when Rickenbacker introduced their first Spanish guitars around 1935—both B-Series lap steel-derived models and the more traditional Ken Roberts model—it was only natural that some of them were equipped as standard with Kauffman Vibrolas.

While the Gibson ES-150—famously played by Charlie Christian—is often considered to be the first electric Spanish guitar, the Rickenbacker Ken Roberts model actually beat the ES-150’s 1936 introduction by a year or more, first appearing in either 1934 or 1935 depending on the source. That said, the Ken Roberts was essentially a rebadged Harmony acoustic guitar with a Rickenbacker horseshoe pickup and Kauffman Vibrola added.

So perhaps technically the first Spanish electric guitar—and by some accounts the first artist signature model electric guitar—although the details of Ken Roberts’s identity have largely been lost to time. But the Ken Roberts model wasn’t the only Rickenbacker Spanish guitar equipped with a Kauffman Vibrola. And it certainly wasn’t the weirdest.

Doc Kauffman had another trick up his sleeve—and another patent to prove it. The patent application makes it clear he developed it alongside Rickenbacker or with them firmly in mind.

Introduced in 1935, the Vibrola Spanish guitar is both brilliant and bizarre. Based on the Bakelite B-Series lap steel, it added the existing Vibrola mechanism…and motorized it.

A variable speed motor controlled by a knob on the guitar’s front drove a pulley-powered cam that moved the Vibrola handle back and forth automatically. The best way to explain the effect is to show you:

You can almost see what Kauffman had been chasing all along—and it makes just how different this first vibrato system was from our modern expectations abundantly clear.

The Ken Roberts model ran until about 1939, with roughly fifty produced. The Spanish Vibrato Guitar survived until around 1940, with probably more than that made…but not many more. And that was the end of that. Until 1958, that is.

Which brings us back to where we started: the launch of the Capri line. So why go back to the Kauffman Vibrola when an objectively better alternative—the Bigsby—was readily available?

There’s no way to know for sure, but we can make a pretty reasonable guess: F.C. Hall never threw anything away. There was likely a dusty box full of the Kauffman units in the stock room, and Hall simply said “Good enough”.

But it wasn’t, really. Not only did it fail to deliver the kind of vibrato players were coming to expect, its tuning stability was…bad. A common joke is that if you breathe on the Kauffman Vibrola wrong the guitar goes out of tune—and that’s not that far from the truth.

Because the string attachment point sits on a spring-loaded pivot, tuning any single string changes the tension across the whole unit—pulling the other strings out of tune. The design was later improved with a second spring on the other side of the unit, but the springs were offset, creating unequal tension and still offering no guarantee the unit would return to its starting position after each use. It’s easy to see why the central pivot approach turned out to be dead end in tremolo design.

These flaws led to the gradual phase-out of the Kauffman in late 1959/early 1960. Its replacement, the Accent Vibrato (click to learn more), was itself a fairly crude design, but still a dramatic improvement.

Despite its relatively short lifespan during the modern era, a number of slightly different Vibrola variants can be found, all attached to the same bracket used on the trapeze tailpiece. The most common is the short-body version seen on the 1958 365 prototype above. There was also a long-body version, seen below and usually found on F-Body guitars (click to learn more), that riveted the short-body version to an extension plate.

A second long-body version was riveted directly to a non-angled trapeze tailpiece blank.

Likewise, some F-Body guitars used the F-Body’s longer trapeze blank as an extension.

In the name of authenticity—certainly not functionality—the 2002-2010 reissue model based on John Lennon’s original 1958 325, the 325C58 (click to learn more), featured a Kauffman Vibrola. Like Lennon did himself, many players have since removed the unit and replaced it with a Bigsby. John Hall had exact reproductions created for the model, although rumor has it that some of the first guitars may have even received leftover originals from the 1958-1960 runs. Just like his father, John doesn’t appear to throw anything away either.

In hindsight, the Kauffman Vibrola is easy to dismiss as an awkward and short-lived experiment. It was unstable, quickly outdated, and ultimately replaced by better designs.

But the Vibrola sits at the very beginning of the vibrato story—a mechanical stepping stone between the lap steel world Rickenbacker came from and the modern electric guitar that would soon follow. It may have been a technological dead end, but it was a historical starting point. And without experiments like Kauffman’s, the tremolo systems we now take for granted might have taken much longer to arrive.

Excellent article, Andy! The video clip provided a great illustration.

The comment about the Halls not throwing anything away brought to mind that a few (?) of the first V63 4001 basses came with real horseshoe pickups, instead of the newly designed reissue HS.