Overview: The First F-Body Guitars (1958-1962)

The guitars that taught Rickenbacker to just be themselves

I would argue that there are two key inflection points in modern Rickenbacker history—the moments when the guitars were most visible in pop culture—that still define the brand’s image in most people’s eyes. The first is the British Invasion era of the mid 1960s, and the second is the college radio/“120 Minutes” era of MTV in the mid 1980s. Statistically, that’s where you probably first saw one.

But F.C. Hall didn’t know any of that would happen when he bought the company in 1953. That market didn’t even exist yet. He just wanted to sell some guitars—to whoever wanted them.

And Rickenbacker’s first modern guitars—the Combo 600 and 800 (click to learn more)—reflect that ethos: “Here, we made a guitar. Do you want one?”

What the Combo 600 and 800—and the later Combo 400—taught Hall was that you needed a target audience first: find out what they want and build it, instead of just throwing something out there and hoping people like it.

So as Roger Rossmeisl spent late 1957 and early 1958 furiously refining what would become the Capri models (click to learn more), Hall was just as furiously loaning those prototypes out and putting them into players’ hands for feedback.

One of the takeaways was that the line Rossmeisl was developing was missing a guitar that appealed to jazz guitarists—which, in the late 1950s, still represented an important part of the market in both prestige and sheer numbers.

At the time, the jazz market still favored conservative, traditional designs—an aesthetic mismatch for Rossmeisl’s bold double-cutaway Capri.

So to fill that gap in the line, a design was sketched out and two prototypes were quickly built for the June 1958 NAMM show. Just like that, the F-Body (for “Full Body”) guitars were born.

Like the Capri line, the F-Body line would consist of eight models—four standard and four deluxe—and it borrowed the Capri’s model numbering scheme, with an “F” tacked on at the end. So if a standard Capri with two pickups and vibrato was a 335, its F-Series counterpart was a 335F.

The two prototypes differed only slightly from the production models, in much the same ways prototype Capris had: the slash soundhole was long with a slightly curved tail, and since neither prototype was equipped with a vibrato, both used an off-the-shelf tailpiece rather than the trapeze fitted to production models. The two-tone pickguard on the 360F prototype is original—a bit of visual flair that wouldn’t carry over to production guitars.

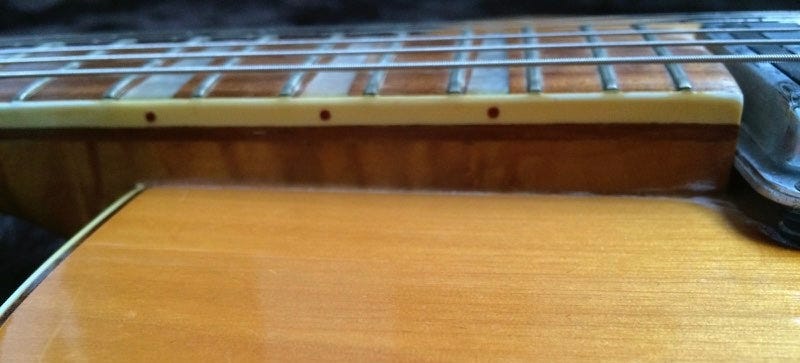

On both the prototype and production guitars, F-Body guitars featured a single rounded cutaway, a 16” wide body, and a 2 1/4” body depth. The deluxe models had the triangle inlays and bound necks found on the Capri models, but added fancier two-ply checkered binding on the body. The standard guitars, by contrast, had no body binding and simple dot inlays—although most retained the bound neck.

All other features—hardware, plastics, electronics—were shared with the Capris. The only exceptions were the tailpieces. Well…kind of.

As you can see, the non-vibrato equipped guitars got a trapeze tailpiece like their Capri counterparts—only stretched out to accommodate the larger body size.

Likewise, vibrato-equipped F-Bodies got the same antiquated Kauffman Vibrola as the Capris, with an extra bracket to extend the unit—without it, the vibrato arm would have ended up behind the bridge! At least two different extension brackets were used with the Kauffman.

Tracking changes to the F-Bodies over their production run is difficult for a few reasons. First, volumes were incredibly low, with perhaps around 150 produced in total over its 1958-1962 run. The Smith book (click to learn more) cites 129, but we all know those numbers are best understood as “directional”.

Secondly, these guitars were largely hand-built—the early ones mostly by Rossmeisl himself, with assistance from Dick Burke—and minor variations abound.

A good example of this instrument-to-instrument variability can be found on the small handful of early guitars with walnut heel caps on the back—and no obvious answer why.

Likewise, while the deluxe guitars launched with two-ply checkered binding, a number of 1958 and 1959 examples have either plain white—like the example above—or two-ply black and white binding. By early 1960 the two-ply checkered binding seems to have returned as the standard.

One of the most obvious changes tells us more than you might realize. Early F-Bodies featured a three-piece maple top and a two-piece maple back. These guitars were constructed the same way as the Capri models: the top was cut out from a solid block and routed out from the rear, with the back attached afterwards.

But given how large these guitars were, that involved a lot of routing. In late 1959 the construction method changed: the top, sides, and back were each built separately, and then assembled together—a much more labor-efficient process. With that shift came a move to a two-piece top.

At around the same time there was also a standardization in the way the neck was set. Some earlier guitars had the neck set at a slight backwards angle—much like a Gibson Les Paul—as commonly found on jazz guitars of the era.

That design choice required the bridge pickup and bridge to be shimmed to the correct height. Longer screws with springs were used on the pickup, and plastic shims were stacked to bring the bridge where it needed to be.

Other guitars had a flat neck set, like all other models in the line. But the change to body construction coincided with a standardization to the neck set—all guitar necks were now set flat. Together, these changes significantly improved manufacturing efficiency, making higher production levels possible.

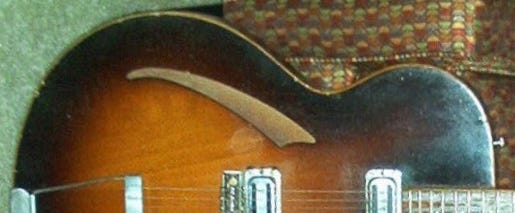

The sharp-eyed among you will have noticed at least three different sizes of soundholes in the pictures above. There’s the long, curved ones on the prototypes:

A shorter one (about 7 1/2”) on the first production guitars:

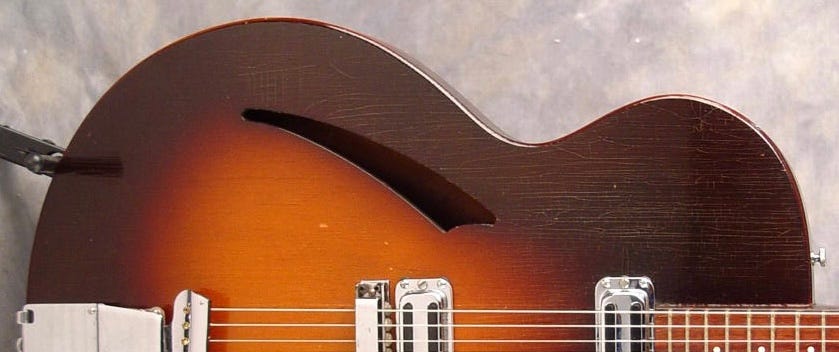

And then the final, 6 1/4” version:

The final version appeared slightly before the change in body construction, so there are a handful of guitars with three-piece tops and the short soundhole.

In 1960, along with the rest of the line, the vibrato-equipped F-Bodies saw the Accent vibrato (click to learn more) replace the outdated and finicky Kauffman Vibrola. Once again the F-Bodies received a stretched version, this time distinguished by cutout musical note embellishments.

1960 would be the high water mark for the F-Body guitars. Production would drop dramatically in 1961 and cease entirely after January 1962. The only changes of note over that time were a decrease in body depth to about two inches in 1961, and the handful built in 1962 would get the fifth “blend” knob (click to learn more).

One especially notable F-Body guitar—a 360F—was produced in 1961 as part of a matched set. A 360F, a 4000 bass, and a Martin 000 28-style acoustic—custom built by Rossmeisl—were all finished in powder blue for Jim Reeves and the Blue Boys. These instruments—and that distinctive color—would later inspire the 2002 Color of the Year (click to learn more) Blue Boy.

As a postscript, at least one 365F was produced in 1964, with two-ply black-and-white binding and period-correct white plastics. Its three-piece body construction strongly suggests it was a leftover body from 1958-59 that was completed in 1964.

So…was the F-Body line a success ? If success is measured in production numbers, the answer is no. F-Body guitars were expensive to build, sold in very small quantities, and quietly exited the catalog after only a few years. By conventional commercial metrics, they were a dead end.

But that framing misses what the F-Bodies actually accomplished.

They helped clarify what it would take to compete in the traditional jazz guitar market. Conservative styling alone wasn’t enough. By the late 1950s, jazz players already had deep brand loyalties, and Rickenbacker was never going to displace Gibson or Epiphone by meeting them on their own turf.

Just as importantly, the F-Body line exposed the practical limits of Rickenbacker’s early construction methods. The mid-run changes to body construction and neck set weren’t cosmetic tweaks; they were hard-earned lessons in efficiency, repeatability, and scale. Those lessons would shape how the company built guitars going forward.

In that sense, the F-Bodies didn’t fail because they were flawed instruments. They failed because they were answering the wrong question. Instead of asking how to make a Rickenbacker fit an existing market, the company soon shifted toward asking what made a Rickenbacker unmistakably itself—and in doing so began to define its niche.

That lesson wouldn’t sit dormant for long. Only a few years later, Rickenbacker would take another run at the “full body” idea with the short-lived F-body revival of 1967–68—a very different experiment, informed directly by what the original F-Series had taught them. We’ll cover those guitars separately, but they make far more sense when viewed as new take—not a resurrection—on the same core idea.

The shift away from tradition and toward identity is what ultimately made the British Invasion guitars possible, and later allowed the brand to resonate again during the college radio and 120 Minutes era. It was the moment Rickenbacker stopped trying to fit in and started learning how to stand apart.

Want to learn more about…everything else? Check out our handy site map to see what we’ve already covered. Don’t see what you’re looking for? Drop it in the comments and we’ll add it to the queue!

re: "The deluxe models had the triangle inlays and bound necks found on the Capri models, but added fancier two-ply checkered binding on the body. The standard guitars, by contrast, had no binding and simple dot inlays."

I guess it depends how you read that, but the standard guitars had bound necks.

Would be cool to add that the binding progressed from black, to black/white, to checked over the run...

Tibor Kovarik

I am blown away with the depth of your knowledge and detailed research. Your articles are well written and captivate the reader right to the end. Keep on writing, you will always have an interested audience.