Overview: The Combo 600 & 800

The launch of the Combo 600 and 800 in 1954 marked the birth of Rickenbacker as we now know it.

Yes, the company traces its roots back to 1931, and yes, Rickenbacker built guitars before 1954. But those instruments belong to a different era—and, in many ways, a different company altogether.

In practical terms, Rickenbacker’s modern era began in 1953, when F.C. Hall purchased the company from Adolph Rickenbacher—and the Combo models that followed would define everything that came next.

Without rehashing the entire pre-history, it’s important to understand why Hall bought Rickenbacker in the first place. As Fender’s sole distributor, Hall was locked into a business where he held no real leverage. He could sell guitars, sure, but he couldn’t set prices, dictate supply, or influence what was built—or when. Buying Rickenbacker was his escape from that imbalance. For the first time, he controlled the entire process.

What he didn’t yet have was anything worth pushing through it.

It’s a common misconception that the Combo 600 and 800 were designed by Roger Rossmeisl. They weren’t. The credit belongs to Hunt Lewis, a commercial industrial designer and director at the California Institute of Technology. Using Hall’s brief for a modern guitar that utilized existing Rickenbacker technology, Lewis delivered a silhouette that the final product remained very true to.

Rossmeisl did, however, arrive at Rickenbacker in early 1954—hired by factory manager Paul Barth—and he did play a role in the 600/800’s birth. Most notably, he refined Lewis’s original design by introducing a German carve (click to learn more) to the top, a visual and tactile detail that would soon become synonymous with Rickenbacker guitars.

This matters, but not in the way it’s usually framed. The Combo 600 and 800 are not “Rossmeisl guitars” in the way later models would be. Instead, they capture a moment of transition: Hall finally had the control he had been seeking, and Rickenbacker—almost accidentally—had begun to articulate a design language it would spend the next decade refining.

To understand that transition let’s look at the guitar’s design, and specifically how Lewis’s original concept was refined once Rossmeisl got his hands on it. The silhouette you see above is very close to Lewis’s drawings—only the treble cutaway has been slightly modified to provide easier access to the higher frets. Lewis called for a “slight crown” to the top, which Rossmeisl either chose to disregard or reinterpret as a full German carve. But the bigger difference lay in how the body was constructed.

Lewis had envisioned a semi-hollow-bodied guitar with a hollowed-out back section and a thin top—essentially the reverse of a modern semi-hollow Rickenbacker. Rossmeisl did the exact opposite. Sort of.

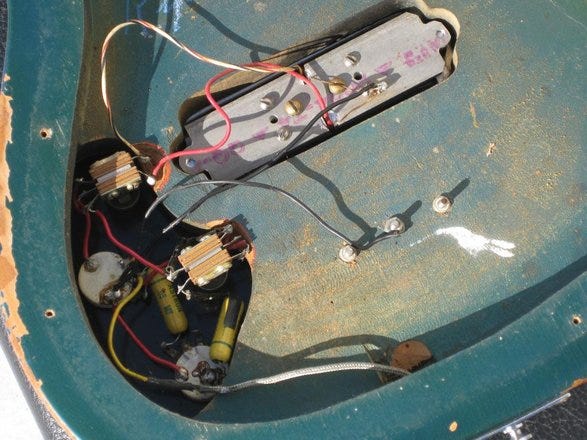

Rather than routing out the beefy two-and-a-half-inch-thick body from the top, Rossmeisl routed it out from the back. And instead of gluing a wooden back in place, the routed out area was covered by a thin metal sheet—sometimes bare metal, sometimes flocked—held on by four wood screws.

Although this may look odd, there was a practical reason for this approach—without a removable cover the wiring and controls would have been completely inaccessible. Over time, as we will see, this facet of construction will change dramatically.

The neck attachment was a strange amalgam of techniques. It was both glued in place—like a Gibson—and bolted on with a single large lag bolt, more akin to Fender’s approach. It proved to be a design dead-end, as no subsequent Rickenbacker models would use this hybrid construction.

Lewis’s original neck design, it should be pointed out, was a novel one. Premade wedges slid onto a T-shaped truss-rod, separated by aluminum spacers that doubled as frets. That idea never made it off the drawing board.

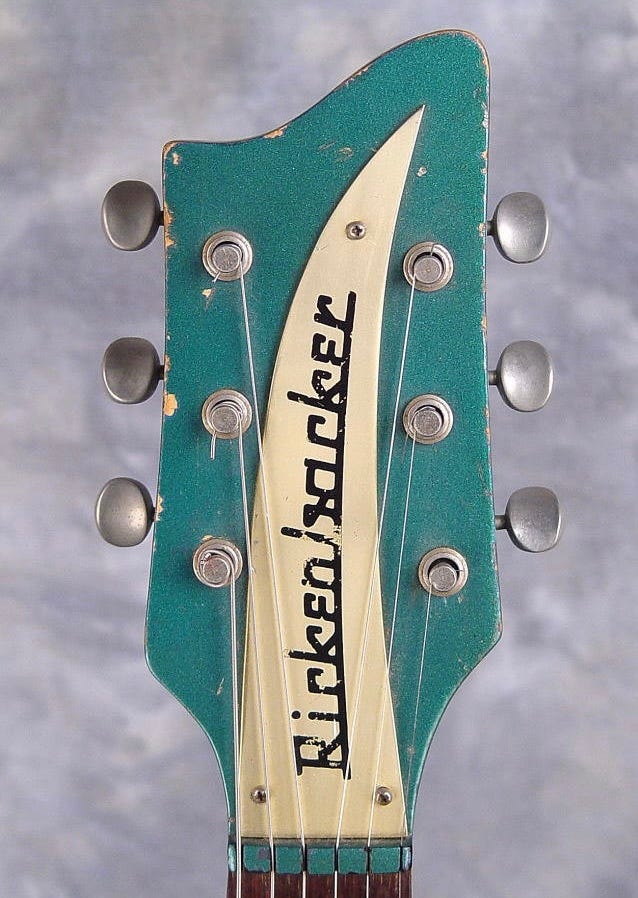

Lewis’s design also included a simple headstock very similar to the “snakehead” design found on Fender Esquire prototypes. That shape does appear on a handful of early prototypes, but Rossmeisl ultimately gave production guitars a flowing swoosh. Tuners were closed-back Kluson Deluxes

While we can already see hints of what would come later in these first modern Rickenbackers, one design detail would prove to be remarkably durable: the truss rod cover shape and logo.

F.C. Hall understood the value of branding from the outset, and one of the very first things he did upon purchasing the company was to commission a modern new logo to rein in Rickenbacker’s previously inconsistent approach to branding (click to learn more).

That logo was given a slight curve to fit the slash/scimitar/whatever-you-want-to-call-it shape Hall’s wife Catherine cut from a piece of paper. It has remained an unmistakable feature of nearly every Rickenbacker since. That said, these first iterations were made of either gold anodized aluminum or black painted aluminum with the logo screen printed on top, as opposed to the backpainted plexiglass covers we are more familiar with today.

And while we’re discussing the truss rod cover, it’s worth talking about what laid beneath. The earliest prototypes featured dual truss rods (click to learn more) running the length of the entire body. The concept didn’t make it to the production guitar—those featured a single hairpin style rod. Still, Rossmeisl clearly wasn’t ready to abandon the idea entirely.

A handful of later production guitars would sport the full length dual rods, and dual hairpin rods—although not through-body—would go on to become a Rickenbacker signature after first appearing on the 4000 bass in 1957.

Other key things to know about these early guitars: the finish was nitrocellulose—Rickenbacker would not switch to its trademark conversion varnish (click to learn more) until 1959. Blonde was the most common color, with Turquoise Blue becoming available in 1956. Usually—but not always—Blonde guitars came with a black anodized aluminum truss rod cover and pickguard, and Turquoise Blue came with a gold anodized truss rod cover and pickguard.

Early bodies were made of ash, alder, and maple, with maple becoming standard fairly early. Necks were maple with unfinished paduak fingerboards.

Knobs (click to learn more) changed multiple times over the guitar’s run—seemingly based on what was available at the time of assembly. Black bakelite “UFO” knobs borrowed from the lap steels were most common at introduction, and chrome knurled knobs borrowed from the console steels were most common by the end of the model’s run.

So everything we’ve said up to this applies to both the Combo 600 and 800. So what, exactly, differentiated the two models?

The electronics.

Rickenbacker already had a pickup—the world’s first electric guitar pickup, in fact—so it made perfect sense that the Combo 600 would feature a single, venerable horseshoe pickup (click to learn more) mounted in the bridge position not unlike that of the Fender Esquire.

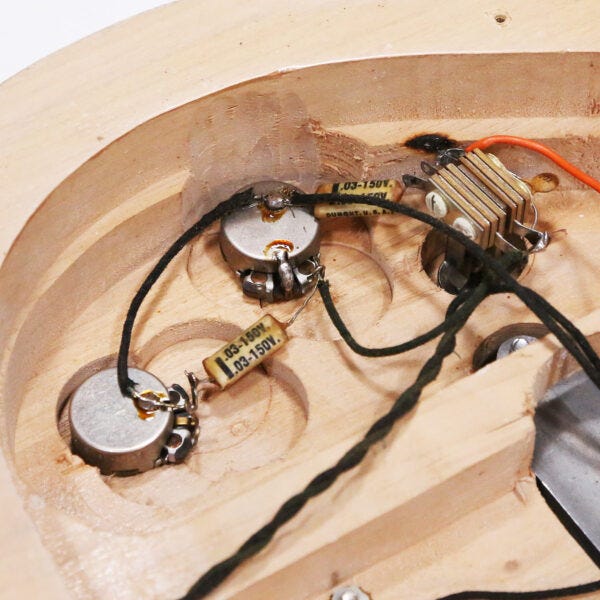

The wiring harness featured a volume control, a tone control, and a three position tone selector. The exact function—and specifications—of that selector however, are difficult to pin down.

The problem is that nearly every photograph I can find of the Combo 600’s wiring harness shows something slightly different, and almost all examples appear to have been modified at some point in their lives. My best guess is that one position engaged a high pass filter for a brighter tone, one engaged a low pass filter for a darker tone, and the last allowed the signal to pass unfiltered to the volume and tone controls. The output jack was located at the butt of the guitar, on a plate shared with the strap button.

The Combo 800 was a completely different matter—even if the only obvious visual difference was a second three-way selector.

What lurked under the Combo 800’s horseshoe magnet, however, was nothing short of a game-changer for the electric guitar—yet one Rickenbacker failed to recognize or capitalize on at the time.

Here’s how period literature described the Combo 800’s wiring package:

“The new Rickenbacker Multiple-Unit pickup…outstanding for tone fidelity, and a tone control circuit which has nine tone combinations, varying from sharp treble for solo work to a rich background and rhythm tones. One three position switch selects the treble or bass pickups or both. The second three pole switch adds more treble or more bass. Both the treble and bass pickups have individual volume controls for greater control of the instrument output.”

Put simply, under that single horseshoe magnet were two pickup coils, mounted side by side, which could be selected individually, or together—in series. Otherwise known as a humbucking pickup.

The humbucker origin story is usually framed as a race between Gibson and Gretsch. But that framing overlooks an inconvenient fact: the Combo 800’s Multiple-Unit pickup beat them both to market—available for purchase while Gibson’s Seth Lover and Gretsch’s Ray Butts were still refining what would become the PAF and Filter’Tron designs

Unlike Gibson and Gretsch, however, Rickenbacker did not aggressively patent or market the Multiple-Unit as a defining innovation and it never became the foundation of a long-running pickup family. As a result, its role in the early history of humbucking design has been overlooked—if not outright forgotten.

This will become an ongoing theme during the early Hall years: Rickenbacker was ahead of the curve in many ways, but not yet coherent—so innovation routinely outpaced the company’s ability to recognize or capitalize on it. In short, Hall may have now owned the process, but he was still learning how to tell the story

Put into that context, Rickenbacker didn’t “lose” the humbucker development race. They just didn’t know enough to tell anybody they were running.

So where did the Multiple-Unit pickup actually come from?

Martin Kelly’s excellent book Rickenbacker Guitars: Pioneer of the Electric Guitar states that F.C. Hall was responsible for its development. But that claim rests on later Hall family histories rather than period documentation. And while Hall was a gifted businessman and distributor, he was not known as an electronics designer.

By contrast, Paul Barth’s fingerprints are all over Rickenbacker’s pickup development from the very beginning. Barth assisted George Beauchamp throughout the development of the original horseshoe pickup, and many historians now believe he carried much of the technical burden of that work. And when the Combo 800—and its Multiple-Unit pickup—was being developed, Barth was…still at Rickenbacker, as the factory manager.

The idea that the company’s first humbucking pickup emerged without Barth’s direct involvement just seems…unlikely. The simplest explanation is also the most persuasive: the Multiple-Unit pickup grew out of the same technical lineage that produced the horseshoe, and it did so under the supervision of the same person…Paul Barth.

The Combo 600 and 800 underwent constant refinement over their relatively short lifespan. Some of it was evolutionary, but much of it amounted to correcting shortcomings in the original design or reworking for more efficient production. Hall’s ambitions demanded scale…and the original guitars simply weren’t designed with scale in mind.

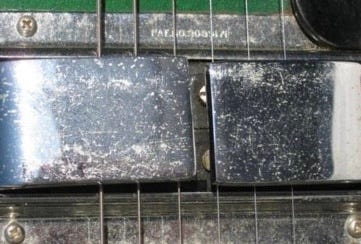

Nowhere is that tension more clear than in the bridge and ashtray cover assembly, which reveals multiple attempts made to at first work around—and finally correct—a fundamental design flaw.

A quick note about tracking changes on these early guitars: precisely dating or ordering these changes can be difficult, as the serial numbering scheme (click to learn more) in use at the time wasn’t yet what we’d call “intelligent”. Still, it’s possible to make some pretty solid assumptions and sketch out a rough timeline.

The root cause that led to the constant modification of the bridge and ashtray assembly was a poor neck set. Look at just how close the fingerboard height is to the guitar’s top on this 1954 Combo 600:

That geometry had consequences. The Combo models saw the introduction of the six-saddle adjustable bridge that—with minor modifications along the way—is still in use on almost all models today. But given the unusually low neck set, it simply didn’t fit. It was too tall.

So the bridge—and the combined bridgeplate/string retainer—had to be countersunk. Then the ashtray cover attachment had to be worked out. Exactly how best to do that took a few tries.

The bridge and bridgeplate above should look quite familiar, but a close examination reveals a great deal. First we can clearly see how the entire assembly is countersunk by roughly a quarter inch. And even that was not enough—it’s decked, and notice how deeply the saddles are notched to provide still more clearance.

This next photo reveal just how crude that rout was—note how half moons were created by hand using a Forstner bit to accommodate the bridge’s locking acorn nuts.

So the bridge is now sunk into the body. How is the ashtray cover attached? We can see from the impression marks in the first photo that it rests on the guitar’s top, not attached to the bridge in any way. The same photo also reveals—upon close examination—a hole drilled in the center of the bridgeplate.

Returning to the second photo, the purpose of the thumbscrew in the middle of the ashtray cover is now clear—to allow the ashtray cover to be bolted directly to the bridgeplate. This is workaround number one for a bad neck set.

This next photo shows a larger and much cleaner rout for the bridge and bridgeplate, but still with fairly significant notches in our saddles. We also see an aluminum frame now screwed directly to the guitar’s face which the ashtray cover clips to—instead of the bridgeplate itself, as originally designed. This is workaround number two.

So at some point they must have fixed the neck, right? Yes—but not until 1957, near the end of the guitars’ lifespan. And here’s another thing: these early guitars were largely built by hand and exhibit some truly shocking instrument-to-instrument variability.

What that means in practice is that you will find guitars prior to 1957 with no bridge routing at all, thanks to a more favorable neck angle, and you will find guitars built after the neck set was corrected that still feature a rout for the bridge.

Other changes were more intentional. To reduce the guitar’s weight, in 1956 the body thickness shrunk from two and a half inches to two and a quarter. At the same time the pickguard grew larger, and the controls moved from being top mounted to pickguard mounted.

You’ll note that the guitar’s German carved top remained unchanged, leaving half of the now larger pickguard “floating”.

With the electronics easily accessible from the front of the guitar, the internal routing now served more as weight relief and evolved as time passed. At first, the rout pattern changed to much more aggressive, to maximize weight relief.

Over time it would become cruder and faster—with the back effectively being “Swiss cheesed” with a Forstner bit.

In late 1957 the body thickness was reduced once again to one and three-quarters inches, eliminating the need for any additional weight relief. The back panel disappeared entirely, as the guitar completed its transition from “semi-hollow” to “weight-relieved” to true solid body.

The thinner, solid body brought with it a revised front as well.

First you’ll notice that the pickguard changed shape yet again—now extending onto the upper cutaway—but more importantly that material changed. The gold anodized aluminum was replaced by gold back-painted plexiglass, a material that would become the brand standard for the next several years.

More notably, however, the German carve was adapted to accommodate this new pickguard. The carve now ends abruptly at the pickguard, leaving the entire treble side of the guitar largely flat.

At roughly the same time, the neck geometry was finally fixed, and the fretboard grew from twenty to twenty-one frets—although the scale did not change. The output jack also moved from the butt of the guitar to today’s more familiar side position. Note that you will find late two and a quarter inch guitars with these two features.

This would be the last major change made to the Combo 600 and 800. While a handful of guitars would continue to be produced into 1959, many of the guitars you find today with 1958 and 1959 serial numbers have components (including bodies!) that clearly were made much earlier than that—cleaning out the parts bin, one supposes.

In hindsight, the Combo 600 and 800 were never intended to be long-lived models. They were experiments—sometimes elegant, sometimes awkward—through which Rickenbacker learned how to translate ambition into a scalable product. Nearly every challenge the company would solve by the end of the decade first surfaced here: neck geometry, access, weight, electronics, manufacturing efficiency, and visual identity.

By 1958, Rickenbacker no longer needed the Combo models. The lessons they taught had already been absorbed into guitars that were lighter, simpler, easier to build, and more visually coherent. But without the Combo 600 and 800—and without the missteps they exposed—there is no cresting-wave body, no 300 Series Capri, no 4000 bass, and no modern Rickenbacker as we understand it today

Find here all the embedded links in this article so you don’t have to scroll back up to find them!

Terminology: Conversion Varnish

Deep Dive: Other Rickenbacker Pickups

Rickenbacker Guitars: Pioneer of the Electric Guitar by Martin & Paul Kelly at amazon.com

Thanks Andy for another enjoyable and informative article about our favorite brand of guitar. Happy New Year to you and yours. Looking forward to a new year and more wonderful articles about our favorite guitars. Cheers.

It’s a shame that the humbucker horseshoe pickup design didn’t make it to the early 4000/4001 basses.

Thanks for the enjoyable and informative article, Andy.

Happy 2026! 🎉