Terminology: The Transitional Era

Not quite vintage, not quite modern

As we discuss in our article on the definition of the word “vintage” (click to read), the experts will tell you that there are two “eras” in Rickenbacker history: “vintage” and “modern”, with 1973 serving as the dividing line between the two. And that dividing line certainly makes sense—we entered 1973 with many vintage specifications still intact, but ended it with modern specs across the entire product line.

But there’s a third, unofficial era that even the experts recognize—the “transitional era”. Because the specification changes that define the shift from vintage to modern guitars didn’t happen all at once. Instead, they unfolded gradually in response to a changing market and new economic realities.

We’re not going to cover each specification change in detail again here—read the vintage article cited above or check the site map for model specific transition timelines (like this one on the 4001’s transition) if you want those details. Instead we’re going to examine the context and address the whys. Sound like fun? Let’s go.

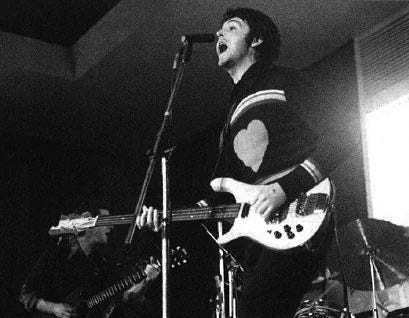

From 1964 to 1966 Rickenbacker quite literally could not make enough guitars to satisfy market demand—thanks largely to a certain band from Liverpool. And by putting even more instruments in The Beatles’ hands—for free—like George Harrison’s 1963 360/12OS, John Lennon’s 1964 325, and Paul McCartney’s 1964 4001S, Rickenbacker only made the situation worse.

While the first half of 1964 was almost completely dedicated to filling export orders for British distributor Rose Morris—who was just barely ahead of the Beatlemania curve—Rickenbacker simultaneously saw domestic demand explode. We have no idea what the backorder log looked like at the end of 1964, but it must have been staggering.

The domestic market was screaming for guitars, and by 1965 Rose Morris was as well. As production shifted towards satisfying the domestic market, Rose Morris orders were consequently delayed—sometimes significantly. The demand on both sides of the Atlantic remained relentless, and Rickenbacker produced instruments as fast as they possibly could. But it just wasn’t enough.

1966 saw production rise to new highs, but cracks were beginning to appear. Relations with Rose Morris had soured over the continuous delays, and on what would prove to be the Beatles’ final tour, only one Rickenbacker would appear—and on only one song: George Harrison’s 1965 360/12 on “If I Needed Someone”. As popular music began to turn heavier, Rickenbacker’s clean chiming sound was starting to lose relevance.

It’s difficult to argue 1967 was a turning point at first glance—it was, after all, Rickenbacker’s highest production year to date. But it was indeed a turning point. Because while 1967 finally allowed the factory to clear up its massive backlog, once those orders were filled the pipeline was suddenly empty. Even Rose Morris cancelled its outstanding orders, bringing the relationship to an end.

Consequently, in 1968 production dropped alarmingly. Something clearly needed to change. So does 1968 mark the beginning of the transitional era?

Most experts would point instead to 1970 or 1971 and I tend to agree. But I would also argue that the foundations of the transitional era first begin to appear in 1968, as Rickenbacker started laying the groundwork for the changes that would follow.

These changes were driven by two clear forces: cost reduction and demand stimulation. Lower production volumes meant fewer guitars over which to spread fixed overhead, making each instrument more expensive to build. Increasing demand could help offset that, but the existing product lineup wasn’t doing the job.

Stimulating demand was the long-term solution, but short-term cost reduction was equally critical—and far easier. And all of that started in 1968.

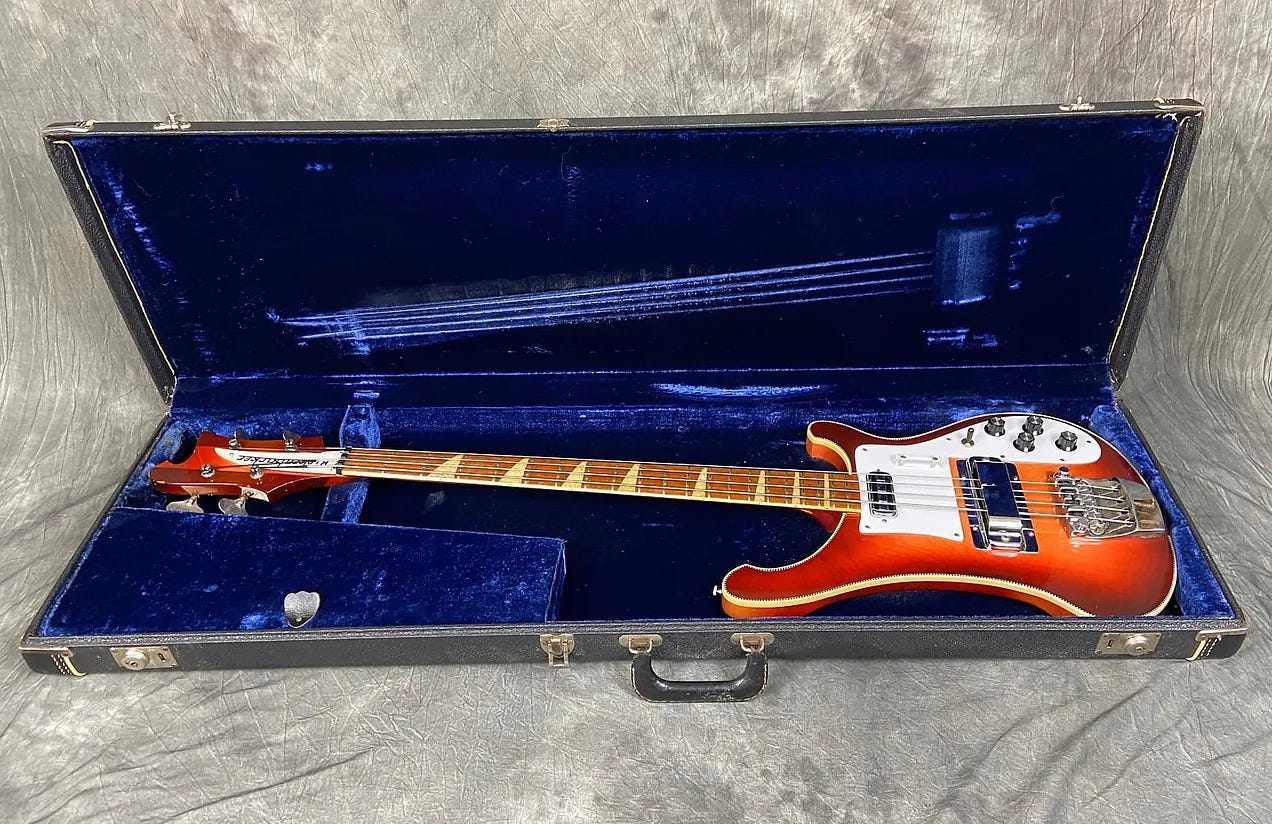

Cases (click to learn more) were one of the first areas to reflect a more cost-conscious approach. Beginning in mid-1968 the standard silver Tolex/blue crushed velvet case was gradually replaced with a lower cost black Tolex/blue velveteen offering.

Sometimes you could kill two birds with one stone. In late 1968, the aged horseshoe pickup (click to learn more) used on the 4001 was replaced with the Higain bass pickup (click to learn more)—both higher-output and less expensive than the horseshoe it replaced.

Cheaper parts. Hotter pickups. These were good things. But the last significant change to the product line had come four years earlier, in 1964, when the round-top “New Style” 360 (click to learn more) had launched—and even that was largely cosmetic. The product line was tired and increasingly ill-suited to the current market. It needed to evolve.

The first truly new guitar since Roger Rossmeisl’s exit in 1962 appeared in 1969—the 381 (click to learn more). That said, the case can be made that it was the “last” Rossmeisl design, as it cobbled together several of his established design elements.

Even so, the production guitar did introduce the “381 Coil” pickup—what we now refer to as the “transitional” or “first-generation” Higain. Designed to have higher output—thus the name—than the toaster that had first appeared in 1957, this new application marked one of Rickenbacker’s first attempts to evolve the line to meet the demands of the modern guitarist.

But the sales slide continued. By 1970 Rickenbacker had reached its nadir, with factory staffing down to just eight employees, down from more than one hundred only a few years earlier. Something needed to happen—and fast.

Thus begins the transitional era.

Higains replace toasters. Twenty-one frets are supplanted by twenty-four (click to learn more). The flagship 360 gets upgraded Grover Rotomatic tuners. Changes meant to make once cutting-edge but now outdated instruments relevant once again.

Double-ply checkered binding is replaced by single-ply white. Neck construction changes to use less expensive woods. Crushed pearl inlays (click to learn more) give way to poured acrylic resin. The sturdy cast aluminum bass bridge is replaced with a zinc alloy version. Changes intended to drive down the cost of goods.

Bound headstocks (click to learn more). Slanted frets (click to learn more). The frequency-sensitive light-up 331 Lightshow. Desperate attempts to do something—anything—to return Rickenbacker to players’ consideration sets.

These are the things we mean when we talk about the transitional era. Sadly, none of the changes meant to spark demand worked. But luckily, they didn’t have to. Basses had been also-rans during the vintage years, but in the early 1970s demand organically exploded—ironically driven largely by two 1964 4001S basses: one Rose Morris 1999 clanking its way through “Roundabout”, and one being flogged across Europe by one of the very same four lads from Liverpool who had originally fueled Rickenbacker’s meteoric rise, but who by then had gone their separate ways.

By 1974 all the significant changes had been made and the transitional era—as well as the vintage era it had consumed—were over. For most of the decade that followed, basses would quietly keep the lights on at Rickenbacker.

Want to learn more about…everything else? Check out our handy site map to see what we’ve already covered. Don’t see what you’re looking for? Drop it in the comments and we’ll add it to the queue!

Find here all the embedded links in this article so you don’t have to scroll back up to find them!

Deep Dive: Other Rickenbacker Pickups

GREAT article, Andy. Very informative!

I would like to add: 1. The aluminum that the bridge pickup was mounted on transitioned to molded black plastic late 1973/early 1974 (?).

2. The 1/2” spacing of the neck pickup from the neck was moved farther from the neck in early 1975 (?).